When researchers at the University of California, Davis, recruited hundreds of fifth graders and their parents for a health and development study in 2006, they planned to monitor the families for at least three years.

Sixteen years later, the California Families Project is still going strong — expanding, as the fifth-graders grew up and had families of their own, from a focus on youth drug risks and resilience to a far-reaching, multigenerational look at overall health and well-being.

The most comprehensive longitudinal study of its kind in the United States, the California Families Project looks at the development of children of Mexican origin and a wide range of characteristics — individual, family, neighborhood, school and culture — that help them succeed in life.

“The overarching goal of the CFP is to understand human development in all its complexity, not to study any particular topic,” said Richard Robins, a distinguished professor of psychology and the project’s director. “We’re trying to understand who you are and how you came to be like that.”

Rather than a singularly focused study, the project involves multiple research teams and takes a “neurons-to-neighborhoods approach” — assessing everything from brain mechanisms all the way up to cultural and neighborhood influences. Robins likens the project to a research center, revolving around data collected over the years from the families.

Importance of studying Mexican-origin families

The concept of the project dates back to the 1980s, when Rand Conger, now a UC Davis distinguished professor emeritus of human ecology, conducted a long-term study of more than 500 families in rural Iowa and how they weathered the Midwest farm crisis of the 1980s.

In the early 2000s, Conger began focusing on Mexican American families in California, who despite their widespread and long-standing presence in the state had been an understudied group.

Previous research on human development focused predominately on white European-background families, Robins said. “We’ve now learned that what we find in certain racial and ethnic groups doesn’t necessarily generalize to all racial and ethnic groups.”

Read more stories about human and animal health

Hispanics make up the largest ethnic group in the state, or about 40% of California’s 39.2 million people, and more than 50% of Californians under age 18. Of Latinos in the state, four-fifths are of Mexican origin.

Camelia Hostinar, an assistant professor of psychology and project collaborator who is leading research on social disconnection in youth and the impact of pandemic-related stress on health, called the California Families Project “a rare and remarkable resource” for developmental scientists.

“This study provides us with unique opportunities to test hypotheses about social and personality development, and the interplay between mental health and physical health, that no other dataset allows,” Hostinar said. “The focus on Mexican-origin participants, an understudied but growing demographic, fills a major gap in knowledge.”

Following lives through time

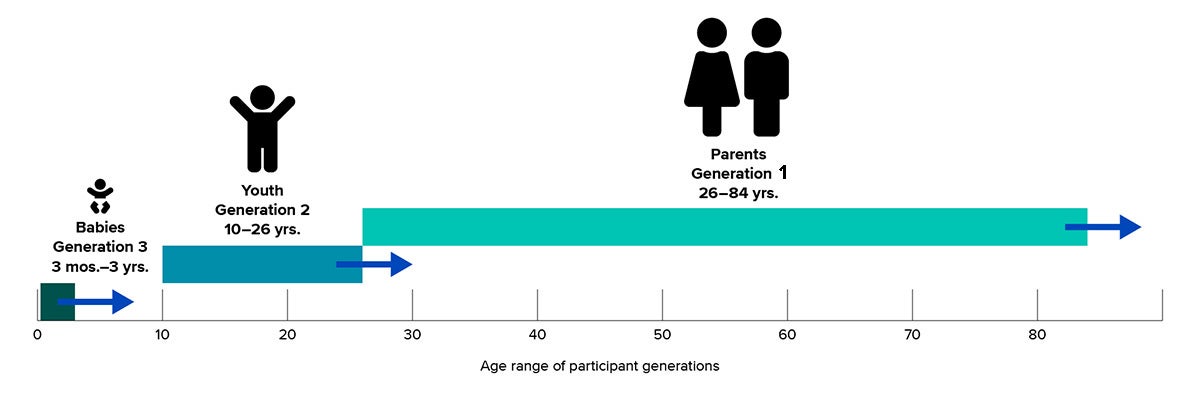

The California Families Project tracks three generations

Resilience factors influence well-being in Mexican American families

The California Families Project aims to develop more effective family- and community-based models for preventing and treating alcohol and drug abuse, improving mental and physical health, raising well-adjusted children and promoting healthy aging.

“With the vast array of data available in the project, we have a unique opportunity to examine how youth remain resilient in the face of adversity, and identify the kinds of factors — biological, psychological, social, and cultural — that nurture healthy development,” Robins said. “These resilience factors can then be targeted in prevention and intervention programs aimed at Mexican-origin youth and their families.”

Health benefits of Mexican culture

Since its start, the California Families Project has received more than $27 million in funding from the National Institutes of Health. Robins and his collaborators at UC Davis and around the world have shared their findings in more than 80 articles in scholarly journals.

The findings are wide-ranging. But significant among them, culture can protect Mexican Americans. Maintaining one’s heritage, researchers found in one segment of the study, may help protect against drug use, delinquency, anxiety, depression and suicidal tendencies.

At the same time, the study explores human traits that may cross cultures, and identifies areas for study in other groups — among them, the development of teen shyness, how brain functioning and mental health relate to risk for substance use, and the toll taken by poverty and other chronic stressors on mental and physical health.

Studying families across all areas of life

Of the 674 fifth graders and their parents who were originally recruited to the California Families Project from Sacramento and Woodland, close to 90% still participate.

Most still live in Sacramento and Yolo counties. About 6% live in other parts of California, and 3% in other states, as far away as Minnesota, Kentucky and Texas. Another 3% live in Mexico. “When they move away, we follow them,” Robins said.

Researchers have collected data from them in 13 waves over the past 16 years — interviewing members of each family for four to six hours over the course of two visits each wave. In some years there have been cognitive tests, a complete psychiatric evaluation, video recording of parent-child interactions and numerous other measurements.

“In the main project, we measure everything from personality traits to parent-child conflict to mental health problems,” Robins said. “We get data from the schools. We get police data for the neighborhoods they are growing up in so we know how much crime is there, and census data to know whether families live in a predominantly Latino community.”

Thanks to a recent agreement with the California Department of Education, the researchers can take an even deeper dive into how the original fifth graders have done in school — accessing achievement test scores, grade-point averages, school disciplinary actions, participation in college prep courses, whether they graduated from high school and other records. These data will allow researchers to better understand, for example, how youth overcome systemic barriers and achieve their educational goals, by identifying sources of resilience in the child, their family, their community and the school context.

Analyzing these complex datasets requires the help of a quantitative expert. Emilio Ferrer, a professor of psychology and co-editor of Statistical Methods for Modeling Human Dynamics, works with project researchers to determine the best statistical models to use.

We’re studying how the youth are developing in this much broader context rather than just one slice of their life." — Richard Robins

“This means we can connect developmental processes across levels, and gain insight into how various risk and resilience factors work together to shape the life trajectories of our participants as they traverse from late childhood through adolescence and into young adulthood,” he added.

Many of the families live below the poverty level. They receive up to a few hundred dollars for their time and trouble each year they participate in the study. However, the payments are not the primary motivation for the families’ participation.

“They know that at some point this will benefit their community,” said Karla Cuadros, who has worked on the project for over a decade and who supervises a team of seven who conduct the interviews in Spanish and English at families’ homes.

Cuadros said that some fathers initially worried about being “lab rats” but are now dedicated participants. Despite various life changes — divorces, family deaths, parent-child estrangements — the families warmly welcome the interviewers into their homes and into their lives, such as when she was invited to a participant’s wedding.

A newsletter sent by project directors to the families in 2018 quoted some of the participants (their names were withheld for study confidentiality reasons). Said one: “I’m so happy our community is making history.” Another said: “It’s amazing to be part of this important project with UC Davis for all these years.”

How does stress affect Mexican American children?

As the families have grown, so has the project. The original fifth graders in the study are now in their mid-20s, many of them with young families of their own.

The arrival of their children led to the 2017 launch of the California Babies Project, which looks at how chronic stress like poverty affects parent-child relationships and the development of the child’s self-regulatory skills.

The research, led by Leah Hibel, a professor of human ecology, is following the children’s development across infancy, toddlerhood and preschool.

Hibel and her team seek to study life as it’s lived — with parents and children wearing watches at night that assess sleep and, three times a day, answering questions via a phone app and taking saliva samples for analysis of their stress hormones. Researchers also visited their homes to observe parent/child interactions.

Initially, the research focused on the effects of poverty on the children’s development. But the COVID-19 pandemic brought sweeping changes to the families’ lives and to the research.

The pandemic magnified stress. Many parents worked essential jobs, facing higher risks of getting sick and dying from COVID-19 and high levels of economic distress. “A huge number lost their jobs due to the pandemic,” Hibel said.

The pandemic interrupted the in-home research for almost a year.

With the help of a UC Davis grant for pandemic-related research, Hibel’s team pivoted to making monthly phone calls to 90 families — about 700 calls in total — to survey them about the psychological and financial toll the pandemic was taking on their lives.

Step one for this project is to further understand the intersection of cultural values and parenting in these Mexican-origin families. How are they parenting right now? How does their culture, beliefs, and value system influence the way that they parent?” — Leah Hibel

Like European-background parents, Mexican-origin parents seek to raise their children to be independent, Hibel said. At the same time, their culture puts family first.

“What we find is that parents who have strong familism values — values of a family connectedness — have more kind, sensitive, cohesive, communicative empathetic relationships with their children,” she said.

What factors are associated with healthy aging?

Researchers are studying the elder generation too, looking at the health and well-being of the parents of the former fifth-graders in the California Families Project. This generation is now predominantly in their 40s to 60s.

This study, launched in 2018, seeks to identify psychological, social, cultural and physical risk factors for dementia and other health problems associated with aging.

Project directors Robins and Angelina Sutin, a professor at Florida State University who earned her psychology doctorate at UC Davis in 2006, are assessing memory, language and other aspects of cognitive function, tracking activity, sleep, medication and health risks, and measuring cholesterol, blood-sugar, inflammation and COVID-19 exposure in over 1,000 people.

In one recent study, they found that the vast majority of the parent generation reported being the recent targets of ethnic discrimination, and that those experiencing higher levels of discrimination performed worse on measures of cognitive function than those experiencing lower levels, indicating that the experience of ethnic discrimination has a detrimental impact on cognitive function.

Another study showed that certain personality traits (conscientiousness and openness to experience) promote better cognitive function, whereas others (neuroticism) promote worse cognitive function, suggesting that we may be able to identify who is at risk for cognitive impairment later in life based on their personality traits earlier in adulthood. This study also showed that individuals experiencing high levels of economic hardship performed worse on measures of cognitive function, but if their economic hardship subsided over time they performed better.

How does adversity affect stress responses?

In a subproject examining neurobiology and depression, 229 participants who had symptoms of depression at age 14 had their brains scanned and underwent physiological tests when they were 17 and again at age 19.

Paul Hastings, professor of psychology, and Amanda Guyer, professor of human ecology, led these studies.

They have found links between brain/body communication patterns, adolescents’ depression symptoms and their experiences of adversity during adolescence.

Types of adversity the researchers examined included family and neighborhood poverty levels, exposure to crime and violence, discrimination and exposure to air and water pollutants — all involving data from the original study.

“We found that youths who experienced chronic poverty that worsened over adolescence had unusually suppressed stress responses. Youths who had not lived in poverty responded to a laboratory challenge with increased physiological activity, as we would expect for well-functioning systems. Growing up in poverty appeared to erode that healthy response pattern,” Guyer said.

Stress response systems appear to continue to be malleable through adolescence, and healthy stress response function could be bolstered by increasing the household income of chronically impoverished adolescents." — Amanda Guyer

The researchers are also investigating differences in how people’s brains respond to reward stimuli, social exclusion and peer pressure, and the links to alcohol use, depression and anxiety.

With a new grant, a team of CFP researchers led by Johnna Swartz, an associate professor of human ecology, will conduct a follow-up study with the participants, who are now in their mid-20s, to identify risk and protective factors associated with the development of depression and physiological wear and tear on their bodies.

Such studies could lead to more effective methods of diagnosing and treating depression — based on biological markers rather than symptoms — as well as tailored interventions for helping youths deal with bullying and substance abuse.

The findings could also guide policymakers in determining the best use of taxpayers’ dollars for social programs, Hastings said.

“If we move more families out of poverty, and mitigate experiences of adversity, we would save billions of dollars in health care costs across the lifespan and increase the amount of money those families would be contributing to overall society,” Hastings said. “Because they would do better in terms of their education and their jobs, there would be long-term gains of investment in poverty alleviation.”

Understanding health and well-being

Robins said working on the project over the past 16 years has been a privilege — and the highlight of his career.

“The California Families Project provides a unique window into the lives of Mexican-origin families and, as we continue to follow these families over time, I hope we will gain a deeper understanding of the factors that contribute to the health and well-being of this vibrant community.”

A cross-disciplinary team

The California Families Project involves researchers from across UC Davis and around the world:

- Richard W. Robins, distinguished professor of psychology and project director

- Rand D. Conger, distinguished professor emeritus of human ecology and project director emeritus

- Angelina R. Sutin, professor at Florida State University’s College of Medicine, a UC Davis alumna (Ph.D. ’06), and director of the Healthy Aging Substudy

- Emilio Ferrer, professor of psychology and project statistician

- Paul D. Hastings, professor of psychology and co-director of the Neurobiology Substudy

- Amanda E. Guyer, professor of human ecology and co-director of the Neurobiology Substudy

- Camelia E. Hostinar, assistant professor of psychology and project researcher

- Johnna R. Swartz, associate professor of human ecology and co-director of the Neurobiology Substudy

- Leah C. Hibel, professor of human ecology and director of the California Babies Project

Other collaborators:

- Alazne Aizpitarte, Open University of Catalonia, Barcelona, Spain

- Guido Alessandri, Sapienza University of Rome

- Olivia Atherton, University of Houston (Ph.D. ’20)

- Brian Armenta, University of Texas at San Antonio

- Mayra Bamaca-Colbert, UC Merced

- Emorie Beck, UC Davis Department of Psychology

- Veronica Benet-Martinez, Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona, Spain (Ph.D. ’95)

- Wiebke Bleidorn, University of Zurich, Switzerland

- Rick Cruz, Arizona State University

- Rodica Damian, University of Houston (Ph.D. ’13)

- Brent Donnellan, Michigan State University (B.S. ’94, Ph.D. ’01)

- Maciel Hernandez, UC Davis Department of Human Ecology (Ph.D., ’14)

- Katherine Lawson, Oberlin College (Ph.D., ’22)

- Monica Martin, Texas Tech University (Ph.D. ’05)

- Elizabeth Muñoz, University of Texas, Austin

- Ulrich Orth, University of Bern, Switzerland (UC Davis postdoctoral researcher, ‘09)

- Eva Pomerantz, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

- Mijke Rhemtulla, UC Davis Department of Psychology

- Gabriela Livas Stein, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

- Zoe Taylor, Purdue University (Ph.D., ’11)

- Kali Trzesniewski, UC Davis Department of Human Ecology (Ph.D., ’03)

- David Weissman, Harvard University (Ph.D. ’18)

- Eunike Wetzel, Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg, Germany

- Emily Willroth, Washington University

Related Stories

Study to Look at Mexican American Family Strengths

In 2005, UC Davis researchers asked 600 Mexican American families in Sacramento what factors help their children to grow up happy and healthy.

Poverty Predicts Stress Levels in Teens, Research Suggests

The UC Davis study measured levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

Research Review Shows Self-Esteem Has Long-Term Benefits

UC Davis researchers reviewed the findings of hundreds of longitudinal studies to determine the influence of self-esteem in many areas of people's lives.

Media Resources

Media Contact:

- Kathleen Holder, UC Davis College of Letters and Science, 530-752-8585, kmholder@ucdavis.edu