A step into Woodland, California’s, Chicago Cafe is an immediate leap into the past.

Customers sit on black swivel stools at a classic diner counter enjoying $12 combination plates heaped with chow mein, pork fried rice, fried shrimp and egg foo young (hot tea and fortune cookie included — cash only).

Regulars know to enter the shotgun-layout restaurant through the kitchen in back, where boisterous cafe owner Paul Fong, 75, greets customers before turning back to cook alongside his wife, Nancy, 67.

Their lone employee, server Dianna Olstad, 57, delivers iced water to tables in throwback red plastic tumblers, sprinkles “honeys” and “sweeties” like salt and pepper, and good-naturedly chides customers who go too long between visits to the cafe.

“She has gotten on me for not showing up,” said Wes Hensley, 36, during a Tuesday lunch in September with his parents, Lori Hensley, 63, and Gene Hensley, 65. A lifelong Woodland resident and Chicago Cafe customer, Wes “probably has only been here a half-dozen times this year,” he admitted somewhat sheepishly. His mom, on the other hand, dines at the cafe at least once a week.

The scene is charmingly — almost cinematically — retro, a reminder of when this Sacramento and Davis suburb of 62,000 was still a small farm town. But the cafe’s significance goes well beyond Woodland, where for families like the Hensleys, it has just always seemed to be there.

UC Davis School of Law Professor Gabriel “Jack” Chin is leading interdisciplinary research into the restaurant, a piece of living history standing amid the vestiges of Woodland’s one-time Chinatown. With a group of students, Chin aims to document the diner’s past and how such institutions reflect the Chinese American experience. After a deep dive into local archives, they have concluded the Chicago Cafe might be the oldest continuously running Chinese restaurant in California and perhaps even the United States.

Researching the nation’s oldest Chinese restaurants

Owned by three generations of the Fong family, the cafe has operated at least since 1910, according to the UC Davis research, or 1903, according to the Fongs and some tantalizing yet unverifiable mentions elsewhere.

In 2022, Chin’s Asian Exclusion Research Project brought together a cohort of law students led by Natasha Kang, J.D. ’23, along with English, comparative literature and history scholars. The students researched the restaurant in the Yolo County Archives, other libraries, online and through interviews. They could not nail down the Chicago Cafe’s 1903 date in part because city directories of the day excluded Asian-owned businesses. But either year of origin establishes the cafe as the longest-running in the state — longer even than San Francisco’s venerable Sam Wo. The 1910 provenance also puts the Woodland cafe in close historical proximity to Butte, Montana’s, Pekin Noodle Parlor, which dates to either 1909 or 1911 and is widely recognized as the nation’s oldest Chinese restaurant.

For any American restaurant to survive for more than a century is remarkable considering the built-in uncertainties of an industry where most businesses don’t make it to five years. But the Woodland and Butte cafes’ longevity is nothing short of extraordinary given the hostile environment Chinese immigrants faced well into the 20th century, the UC Davis scholars assert in their new paper “Symbols of Survival: Finding the Oldest Chinese Restaurants in the United States.”

The paper details how a “racist federal immigration regime” kept Chinese immigrants from becoming citizens or outright banned them from immigrating. As Chin previously explored in his widely publicized 2018 Duke Law Journal article “The War Against Chinese Restaurants,” dining establishments were a particular target of legal and union-led efforts to limit business competition.

Yet Chinese restaurants, conversely, also offered a “rare economic lifeline,” Chin explained.

“Chinese restaurants were a business that, at least according to some courts in some periods, allowed Chinese people to immigrate notwithstanding the Chinese exclusion laws. Because merchants were allowed to immigrate. And some courts held that Chinese restaurant operators were merchants.”

That “merchant” designation came with tight restrictions: Chinese restaurant owners were not to engage in manual labor. They could write checks to vendors, but not wait on customers, or cook. As Chin noted in the new paper: “An immigrant Wolfgang Puck or Gordon Ramsay of a century ago could secure their status through naturalization,” but if equally famous, Chinese-born chef and UC Davis alum Martin Yan ’73, M.S. ’77, had arrived in the United States in 1915, he would have been “subject to deportation if he picked up a wok.”

The ongoing Asian Exclusion Research Project aims to publish specific academic works like the new paper while creating a database of “some of the basic materials about Asian exclusion” for scholarly, journalistic and legislative reference, Chin said. A prolific, oft-cited scholar of immigration law, criminal procedure and race and the law, Chin has investigated examples of Asian exclusion throughout his three decades in the legal academy. In 2014, Chin and the law school’s Asian Pacific American Law Students Association successfully petitioned the California Supreme Court to posthumously admit Hon Yen Chang, a lawyer denied the right to practice in the 1800s, to the state bar.

The Fong family history: Family business, heritage and Chinese-American resilience

The Fong family, like Yan, hails from China’s Guangdong province. Paul and Nancy arrived in the 1970s as part of the family’s staggered entry into the U.S.

“When my great-grandfather was an adult, that’s when he came over and ran the restaurant,” said Andy Fong, 44, who is Paul and Nancy’s son and the family’s unofficial historian. “The rest of [his] family was still in China. When my grandpa got to a certain age in his adulthood, he came over, and he started working in the restaurant. Then my parents finally came over.”

The Fongs “really used this as a platform for immigration and becoming part of the larger community,” Chin said. But aspects of the cafe’s history inevitably were lost to time. Like the origins of its Midwestern name.

“My grandfather opened it, and everybody asks me the question, ‘Why do they call it ‘Chicago’?’” Paul Fong said during a rare break from work at the cafe on that Tuesday. “I have no idea. That was 120 years ago. Maybe he came [via] Chicago.” (The UC Davis research shows the name “Chicago” was used in association with Chinese restaurants in various parts of the country.)

What’s more certain is that the tradition of successive generations of Fongs assuming ownership will stop with Paul and Nancy.

Andy Fong lives in the Bay Area, where he works in tech as a quality engineer. His sister, Amy, 46, lives in Woodland but has her own career as a doctor of physical therapy.

“They both say, ‘You work in the restaurant, you’re going to work 13-, 14-hour days,’” Paul Fong said of Andy and Amy. “They both have good jobs and raised a family, and I am glad for that.”

Andy, who like his sister went to the restaurant rather than home each day after school, and swept floors and washed dishes, recalls a specific conversation with his father when he was young.

“He sat my sister and I down and said, ‘Hey, you guys are going to go to college. You are not going to do what I am doing.’”

Observed Chin: “There is an irony here that in some sense, the reason you have a Chinese restaurant is solely so that your kids don’t have to work in a Chinese restaurant. And that’s wonderful that the [Fong] kids have charted their own path. But historic Chinese restaurants are still important, and there should be one in downtown Woodland.”

With the new paper, Chin, a longtime Chicago Cafe customer partial to its “Chicago combination” plate, wants to get the word out about the cafe’s significance, so one day it will be mentioned in the same breath as Pekin Noodle Parlor or Sam Wo. He said he also hopes the research paper grabs the attention of potential new Chicago Cafe owners, because Paul and Nancy Fong could retire any day now.

“I think it is something an entrepreneur interested in Chinese cuisine and Asian American history could really make their own,” Chin said. He envisions an established restaurateur turning the diner — already so inherently, distinctively cool — into a destination for “foodies” from Northern California and beyond.

No matter what happens with the restaurant space, the Fongs’ absence would be sorely felt in Woodland.

“Every time they close down and go on vacation, they are just swamped when they open again,” Amy Fong said. “People will Facebook Messenger me and say, ‘Hey, we notice that your dad and mom are closed. Are they OK?’

“I think the big niche that we have with our customers is that the roots have been so deep.”

A Chinese restaurant steeped in California history

On this September day, Paul Fong moved between kitchen and dining room, chatting with regulars like David Shaffer, 59, who sat at the counter eating pork noodles. Shaffer said he first visited the cafe as a child with his uncle; he likes how the Fongs serve “the old type of Chinese food.”

Wes Hensley, the lifelong customer, noted that “one of the cool things” about entering through the cafe’s kitchen is seeing Paul and Nancy make everything fresh. This extends to American offerings like a hot sandwich prepared from whole turkeys roasted in house, and breakfast items available all day.

Most other Chinese food in town is “like fast food,” Hensley said.

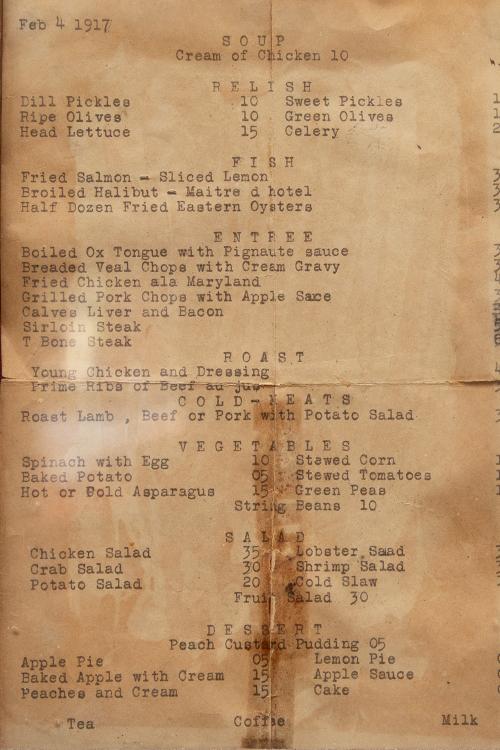

Chicago Cafe’s “old type” of Chinese food, with its various iterations of egg foo young and chow mein laden with bean sprouts, is a specific type developed to appeal to American tastes in the early to mid-20th century. The cafe’s menu has barely changed since the 1950s, Andy Fong said.

This tracks with research conducted by Ben Ruilin Fong, a UC Davis comparative literature Ph.D. candidate and member of Chin’s research team. For his Ph.D., Fong has studied UC Davis’ vast collection of English-language Chinese cookbooks and, with funding from the UC Davis Humanities Institute, collected oral histories in San Francisco’s Chinatown. He also interviewed Andy Fong for the Chicago Cafe project.

“There is just so much interesting and compelling overlap with what was going on in San Francisco’s Chinatown during the 1960s and the story of the Chicago Cafe,” Ben Fong said. For instance, most Chinatown residents who immigrated before 1980 came from Guangdong’s small Taishan region, like Chicago Cafe’s owners. Landing in Woodland rather than San Francisco might have played a role in the Fongs’ business longevity, he said.

Not only is competition far more intense in San Francisco, but “the city has a long history of tearing things down and inserting itself into communities, which could disrupt a restaurant’s existence,” Ben Fong said. But in Woodland, the Fongs’ restaurant “created this kind of positive feedback loop, where people have a familiarity with Chicago Cafe, and have been going there for big periods of their lives, so it makes sense to keep going there. It is not as uncertain or as hectic as San Francisco’s Chinatown feels sometimes.”

Embracing Chinese-American identity

Chicago Cafe has roasted whole turkeys for at least 63 years, according to a 1960 Oakland Tribune column unearthed by Chin’s research. It reported on a cheeky turkey thief who absconded with a just-cooked bird from the Chicago Cafe’s kitchen, only to later return the now-meatless bones with a thank-you note.

Other vintage newspaper reports and ads were less lighthearted, and less apocryphal. In 1910, the Daily Democrat editorialized that every Chinese or Japanese person hired for agricultural work “drove a white man out of the orchard.” A 1919 ad for the Woodland Steam Laundry boasted of employing “white help only.”

Andy Fong said he never heard his father or grandparents discuss facing particular challenges doing business as Asian Americans in primarily white and Latino Woodland.

“We didn’t have a lot of those philosophical or societal kind of discussions,” he said. “I have definitely had it with my friends … But with my parents, that never came up.”

U.S. Census figures place Woodland’s current Asian American population at 8.5%. But there were “less than a handful” of families in town when he grew up, Andy said. A few also were restaurateurs named Fong. At least one was related. He called them all “uncle” regardless.

Those other restaurants are gone now, but his parents’ place still closes on Thursdays, a throwback to when the town’s Chinese restaurants alternated days off so no Woodlander had to go a day without chow mein. Those other restaurateurs often spent days off in the Chicago Cafe’s kitchen, drinking tea and gabbing with the owners.

Growing up in this atmosphere “kind of immersed me in the heritage and the culture,” Amy Fong said, especially when her “very, very traditional” grandparents still ran the cafe. In high school, she won praise for writing assignments focused on being Chinese.

It took Andy a bit longer to fully embrace his Chinese American identity.

“There was a period where I was like, ‘Oh, I wish I didn’t have to go to the restaurant after school,’” he said. “It wasn’t the same as my classmates. … There were times I felt like the oddball out because I didn’t have Asian friends.” And schoolmates sometimes jokingly called him “Bruce Lee.”

Once he left Woodland for college at San Jose State, he met more Asian Americans and gained perspective, Andy said.

He since has visited Taishan twice and become involved with the Friends of Roots nonprofit, which he said helps “people who, unlike me, were several generations away” from China to connect with their ancestral homes.

He now fully “understands how special our restaurant was, and is,” Andy said. “It is part of American history, right? Chinese American history is American history. And it still is that kind of historical place that can be witnessed right now.”

Not just witnessed, but touched and tasted, on any day of the week except Thursday.

Media Resources

Media Contacts:

- Karen Nikos-Rose, News and Media Relations, 530-219-5472, kmnikos@ucdavis.edu

- Carla Meyer, School of Law, 415-385-5110, cmeyer@ucdavis.edu

Press kit with images for media use