- Whisky Science: A Condensed Distillation

- By Gregory H. Miller, professor, Department of Chemical Engineering

- Springer International Publishing, 2019

“Making the connections between chemistry, history and other scientific endeavors and what you’re drinking makes for a more satisfying experience.” — Greg Miller

For chemical engineering professor Greg Miller, whiskey is serious business. A licensed distiller and whiskey enthusiast, his new book Whisky Science: A Condensed Distillation is the culmination of a five-year search for the science behind the spirit, bringing together 300-plus years of history, chemistry and distillation methods.

IS IT WHISKEY OR WHISKY?

According to Miller, "If you go back 100 years, Americans used 'whisky' and the English used 'whiskey.' Somewhere along the line it switched. ... I decided to go with the traditional.”

“You don’t need science to make good whiskey, but knowing what’s going on at a chemical level is helpful if you want to make it taste better, nudge a certain flavor profile or fix it if something goes wrong,” he said.

Chemical engineering and whiskey have been closely linked throughout their history. Before oil, whiskey was the big business. Through the mid-1800s, at least half of the U.S. government’s revenue came from alcohol taxes and tariffs from imported alcohol, which meant supplying such a demand required cutting-edge industrial production techniques that helped birth the field.

“You can argue that distillation was the first industrial process that used what we know as chemical engineering,” he said. “The seminal papers on a lot of the classical chemical engineering things we teach were all focused on alcohol.”

Unknown science

Many of the methods developed at the time are still in use by the world’s largest distillers, though the science behind these methods is either unknown or not widely disseminated.

“It’s a lot like cooking in that once you figure out a procedure for doing it, you teach that procedure without knowing what the chemistry is,” he said. “And if you work out a cooking procedure for your secret recipe, you’re not going to share it with everybody because that’s your secret sauce.”

While tasting whiskey with some friends, Miller was struck by an unusual peppery flavor in one sample. He became curious how to produce that flavor, and why one whiskey had it while others didn’t. When he wrote to the manufacturer, asked around at a trade show and searched for answers online, he realized there wasn’t an easy answer.

“If you were a soft drink company and you made something that tasted weird, you’d get to the bottom of that, you’d fix it and then the knowledge would filter out,” he said. “I thought it had to be the same in the whiskey world, but it wasn’t easy to find.”

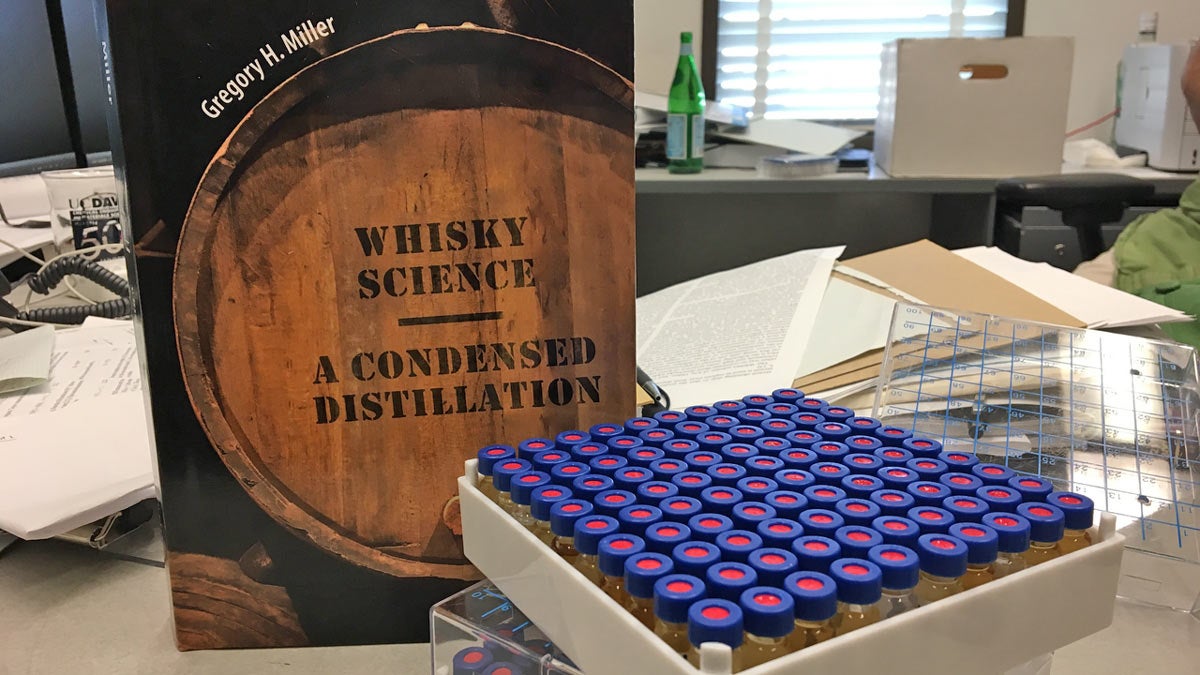

This started him on a quest to figure out what the whiskey world knew and compile it all in one place. He began searching and collecting everything from different distillation methods, anecdotal information and old diagrams in Latin from scientists like Johannes Kepler. The quest turned into his book, published in September 2019.

“It turns out there are enormous gaps in our knowledge and “I thought, ‘These are questions that we have to know,’” he said. “There are a lot of opportunities for future research that are laid bare by putting together a compilation like this.”

Miller plans to use the book as a graduate-level textbook for students interested in the whiskey business. In addition, he has expanded whiskey science education at UC Davis through his ECH 198 course in distillation with Professor Michael Toney from the Department of Chemistry. Though whiskey takes three to four years to make, they walk students through all the different steps over the course of a quarter, demonstrating how the flavors evolve along the way.

“Making the connections between chemistry, history and other scientific endeavors and what you’re drinking makes for a more satisfying experience,” he said. “I really believe that.”

This article was originally published on the website of the Department of Chemical Engineering.