Studying Sharks in San Francisco Bay

On a recent day in San Francisco Bay, a team of researchers took to the waters in search of sharks. Led by Meghan Holst, a Ph.D. candidate in conservation ecology, the group set out to collect data on a variety of species for several concurrent studies.

For her dissertation, Holst, who has a background in public aquariums, is studying the broadnose sevengill shark, an apex predator found in abundance in San Francisco Bay.

Habitat for sharks

Holst is investigating San Francisco Bay as a pupping and nursing ground for sevengill sharks — meaning that females come and give birth there and the juveniles stay for periods of time.

“I want to demonstrate how we are meeting the criteria for the species,” Holst said. “It will be the first time that’s really been defined for this population.”

The sevengill shark species

Holst is also looking at the physiological process that happens when sevengill sharks are caught and released. “Preliminary data is demonstrating that they are pretty hardy, which is really, really good news,” she said.

She has also connected with local anglers and will show the importance of working with them. “I have found they have a lot better understanding of this population than most of the people who study them.”

Undergraduate research opportunity

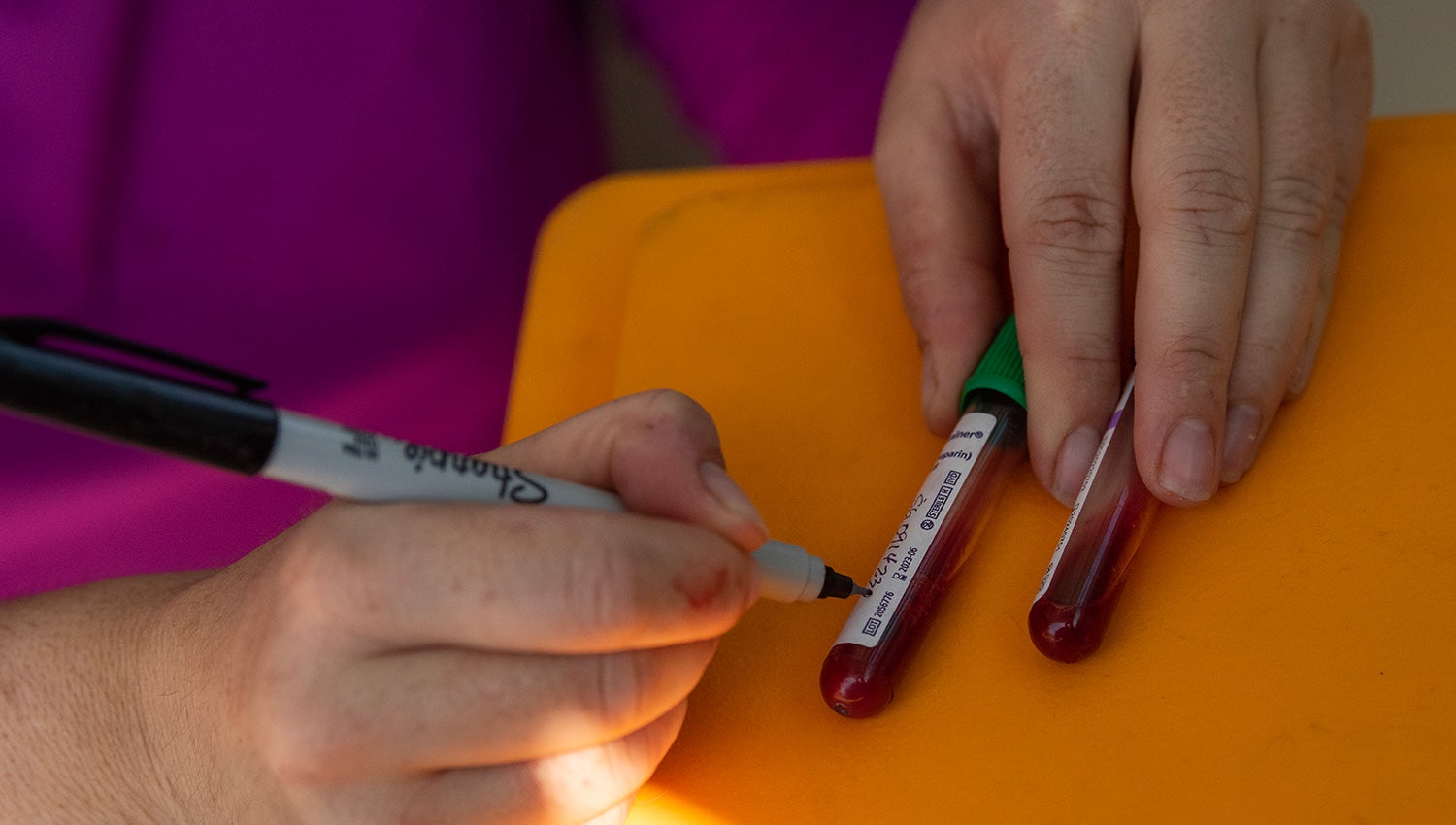

To help gather the data needed, Holst connected with Kimberly Stauffer, a graduating third-year animal biology major from Riverside County (pictured right). Stauffer helps restrain the sharks, take measurements, gather blood and tissue samples and release the sharks.

“That’s my favorite part — being able to do fieldwork,” Stauffer said. “You’re going out into the field and actually seeing what you’re studying. It’s pretty rewarding.”

Helping determine a career path

Stauffer is writing her senior thesis on juvenile sevengill sharks, investigating behavior and eating habits. “As an undergrad, everything is pretty interesting because it’s all new,” she said. “Sharks are cool, but also I haven’t really worked with fish, so it was a whole new domain. I felt like there was a lot to learn.”

The project has awakened a love for marine science. After graduation, she said she’d like to continue research work, go to grad school and work for a government organization.

Interdisciplinary shark research

The data gathered in the future could offer much-needed background for a species labeled as vulnerable by the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species.

Additional data on other species, including the leopard shark, will go toward other collaborations Holst has with partner organizations and groups.

“I really rely on interdisciplinary work to get enough data to investigate anything,” Holst said. “There are several collaborations that are always running.”

Catch and release — with apex predators

Back in San Francisco Bay, the group caught a variety of sevengill and leopard sharks, releasing them quickly. Holst expects to finish her Ph.D. in the spring.

“Sevengill sharks typically live 200 to 300 meters in the water, and San Francisco Bay is a unique habitat where we get access to them in a shallow habitat because they visit here for part of their life cycle,” Holst said. “It’s a really special place.”