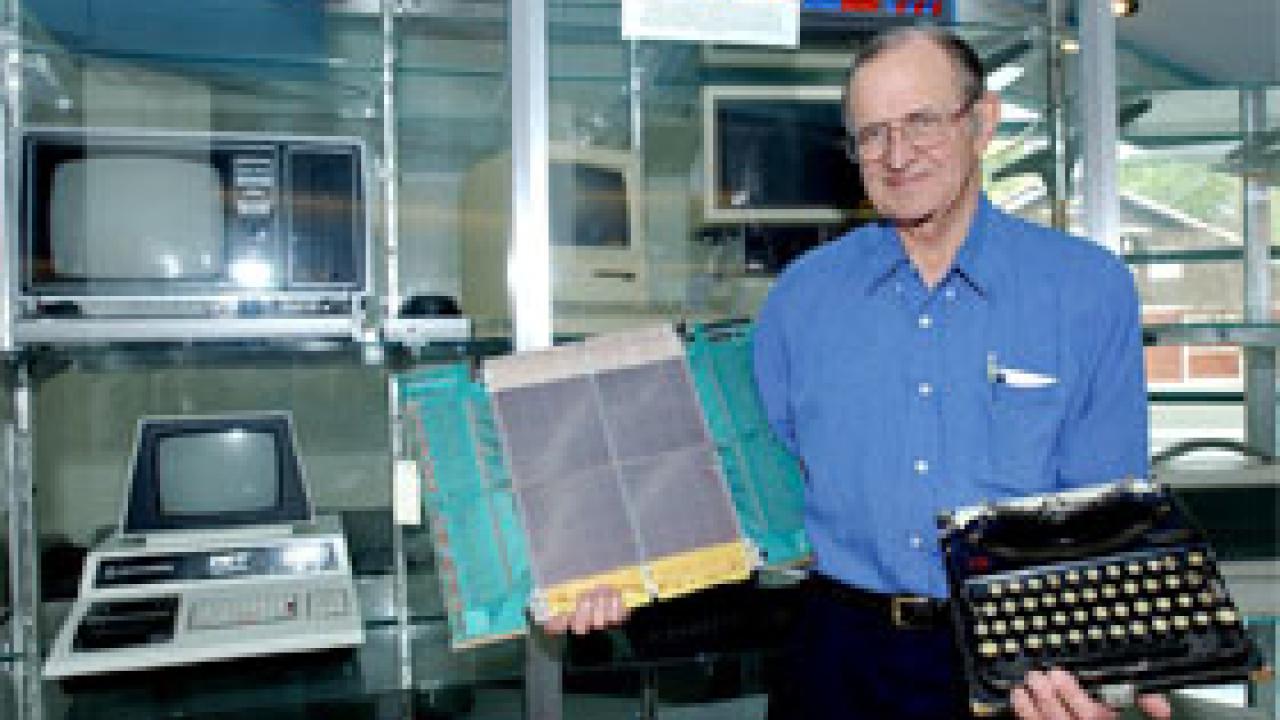

With computers as ubiquitous as light bulbs, it is hard to imagine that as recently as the 1970s UC proposed buying just two computers to serve the entire system. Richard Walters, professor emeritus of computer science, has seen that history, and some of it is reflected in the campus computer museum he has helped to create.

The collection, part of which is on display in the foyer of Kemper Hall, might trigger some nostalgia for those who can remember when floppy disks really were floppy.

"There's been a revolution in the size and power of computers," Walters said.

Walters, who began his scientific career as a geologist, got interested in computers while working in the oil industry. After helping to set up the computer research department at Exxon, he joined the UC Davis School of Medicine in 1967 with ideas about using computers in medical research and teaching.

One of the first major projects was to computerize the Human Performance Laboratory in Hickey Gym. In the late 1960s, the lab acquired a Raytheon 703 minicomputer made up of three or four racks the size of large filing cabinets hooked together with a maze of thick black cables, recalled Wylie Harter, a hardware designer in the lab from 1968 to 1978.

The machine's central processing unit "filled a big drawer and looked like a ball of spaghetti, but we could actually modify or add commands by changing the wiring," something that's impossible with CPUs on a chip, he said. "It was a whole lot less capable, but a lot more accessible," Harter said. "You could get very close to the machine."

The Raytheon 703 computer was used for collecting data and calculating results in real time, such as acquiring heart rate and oxygen consumption data during exercise. Using interfaces and controllers designed in the lab, it was also used to control pedal resistance of exercise bicycles and the speed and elevation of the lab's large treadmill.

The research data obtained with the Raytheon system opened the door to the sort of portable stress testing equipment now found in any cardiology clinic, said Ed Bernauer, professor emeritus of exercise science.

"It revolutionized the procedures used in calorimetry (the study of heat released or absorbed in a chemical reaction) and allowed the collection of respiratory metabolic data that is standard practice in stress testing today," Bernauer said.

Long before cell phones and Blackberrys, lab researchers carried out some wireless experiments, collecting data from athletes running on the track and transmitting it back to the computer by radio.

"We had nothing like the data rates available now, but we were doing it," Harter said.

At the campus level, in 1969 UC Davis acquired a Burroughs mainframe computer. The machine could run multiple jobs at the same time, allowing users to "timeshare" on the computer. "It revolutionized the way the campus used computers," Walters said of the Burroughs computer, which occupied most of a room in the basement of Hutchison Hall.

Data were input from tape reels or punch cards, recalled Rodger Hess, who in 1979 was hired as a consultant programmer on the machine. Transferring data to another computer meant loading it onto a reel of magnetic tape and carrying it across campus.

The machine also had 12 dial-in modems capable of 110 baud (bits per second). One of those modems, made of wood, still sits on Hess' shelf at his desk in Communication Resources. In addition, part of the machine's core memory, made of tiny iron rings threaded on wires, is on display in the museum.

Machines of the era could also be temperamental. Ken Komoto, who joined the UC Davis Computer Center in 1966 and is now a programmer in the Registrar's office, recalls installing shields on the Burroughs to stop stray body parts from knocking against switches and upsetting the program.

In dry weather, the Raytheon computer would stop working if programmer Gail Nishimoto got too close to it.

"I was hanging around the machine a lot because I was interested in programming," she said. "You would hear a spark and it would stop."

The problem was quickly traced to static electricity from her nylon petticoat and stockings. "It was a pretty interesting problem, but it was alright if I didn't get too close to it," Nishimoto said.

With a series of upgrades, the Burroughs machine operated until 1988, running the "General Ledger" program for university accounting. It was also used for research work including engineering simulations. General Ledger continued to run on a smaller computer until the early 1990s, when it was replaced by DaFIS running on Unix computers. The student records system, Banner, began running on Unix machines in 1988.

By the mid-1980s, personal computers made by Apple, Franklin (an Apple clone), IBM, Osborne, Data General and Kaypro were proliferating on campus, and some of these machines with 64 kilobytes of RAM are represented in the museum. Early forerunners of the laptop included the Osborne portable, small enough to fit under an airline seat but a little heavy at 24 pounds.

At the time, UC Davis began transferring many of its computing functions to smaller machines, especially Unix-based systems, said Larry Johnson, another Computer Center veteran. In doing so, the Davis campus was moving in the opposite direction from the UC Office of the President and some other UC campuses that were buying large IBM systems. UC Davis was operating a Burroughs system incompatible with IBM and had a much smaller budget. But that decision left UC Davis in a much stronger position in the long run, as computers got smaller, cheaper and more powerful, Johnson said.

Computing power and memory size has grown exponentially. Students now register online and, starting last quarter, instructors began entering grades online. While some habits take a while to change, using computers is a given to the younger generations of faculty and staff.

"We've come a long way," said Komoto. "We would have two or three people tending one computer in the computer center; now you can have one person and 30 or 40 computers."

"It used to be that the only people who used computers were intensely technical," said Hess. "Now it can be an accessory discipline."

"I hate to use the term, but it is a paradigm shift," Komoto said.

The amount of information that can be stored and moved easily is now so enormous that the next wave in computing will be in software to deal with such large volumes of information, Walters said.

"We've had an information revolution, but we don't know how to handle the information we have," he said.

Harter, who left UC Davis in 1978, feels that though computing power has increased enormously, some of the romance has been lost. On a Picnic Day visit to Hickey gym, he found the big old Raytheon, and its jungle of big black cables, gone -- replaced by desktop PCs.

"It's just not the same atmosphere," he said.

Media Resources

Andy Fell, Research news (emphasis: biological and physical sciences, and engineering), 530-752-4533, ahfell@ucdavis.edu