July is here, and that means hot dogs on the grill, bodies at the beach and on TV the cycling epic known as the Tour de France.

But the Tour de France is no day at the beach. One of the most challenging sporting events worldwide, the 23-day cycling marathon that ends July 24 covers a different route every year. This year's 2,241 mile-course takes riders through rolling farmland, brutal mountains, cobblestone streets and unpredictable weather.

What does it take to win such an event? That question was recently posed to a number of nationally renowned UC Davis experts in sports medicine, psychology and physiology. To be a champion — like six-time tour winner Lance Armstrong, who was headed for a seventh consecutive yellow jersey as Dateline went to press — the body and mind must work together. And work hard.

Eric Heiden, Olympic speed skating champion and UC Davis assistant professor of sports medicine, says that training, strategy and preparation are the cornerstones to success. He should know — he has been there.

"You need to have a strong team around you and be a good climber on the mountains," said Heiden, who won a record-breaking five individual gold medals in speed skating at the 1980 Olympics in Lake Placid, N.Y. "You need to be economical in your efforts, taking advantage of gaining time between the stages."

Heiden got involved in cycling after his Olympic days, winning the U.S. Pro championship in 1985 and competing in the Tour de France the following year.

For Heiden, competing in the tour was a memory of a lifetime for an athlete with many gold-plated memories. "It was an eye-opening experience," he said. "It was the hardest physical endeavor I ever undertook."

He did well, but said the mountains were a particular challenge for him. "I'm heavy-legged," said Heiden, "and so I suffered on the mountains" where rail-thin specimens like Armstrong gain time on their opponents.

As Heiden explained, Tour de France cyclists are riding between four to six hours a day, consuming a great amount of calories (5,000 to 7,000), and hydrating themselves with liquids. With some days involving 150 miles of riding, says Heiden, "You don't want to get behind on the hydration."

He noted that most cyclists start training exclusively for the Tour de France the previous December. Many racers do not worry about winning the other cycling races that start in February, using them instead for training for the Tour de France.

Then there's the mental aspect.

Ross Flowers, a UC Davis psychologist in Counseling and Psychological Services and the director of the Sport Psychology unit for the university's Intercollegiate Athletics Department, says athletic success depends on the right mind set. And achieving this may be harder than it sounds.

'Great patience'

"The cyclists need clarity in both their minds and bodies," he said. "Competitions like these require great patience and a rejuvenating spirit to make it through all the ups and downs. They need to maintain an intensity over a long period of time."

Flowers himself knows about breaking through mental barriers. In high school, he was a Washington state champion and All-American in the 110-meter hurdles. Later, at UCLA, he became an All-American and Pac-10 champion, overcoming the physical, mental and emotional aspects of a serious injury as a freshman.

He talks about using "distraction methods" for masking the physical discomfort associated with high-energy cycling. Examples of distraction include focusing on the scenery and spectators while engaged in the activity. "It takes you away from the way your body may be feeling," said Flowers.

As for Armstrong, Flowers noted that the cyclist overcame a near-fatal case of cancer several years ago and has since strung together a record six consecutive Tour de France victories. "He obviously has a very strong spirit," he said. "His own life experience has given him a great mental ability."

Visualization

Paul Salitsky, a UC Davis lecturer in exercise biology, studies the psychological aspects of sports and exercise.

"To have reached that level in cycling reveals a great deal of mental toughness," said Salitsky, who describes himself as a "mental strength" coach. "Sports psychology is looked more favorably upon by athletes and society than it was 10 or 20 years ago."

In competing in the Tour de France, Salitsky said, the best cyclists will concentrate and focus their minds, display mental toughness and a relentless sense of not giving up, and use visualization. Of the latter, he says, visualization is akin to using "the brain like a recorder."

For example, the night before an event a cyclist may close his eyes and visualize how to successfully move through every step and detail of the next day's course challenge.

"The brain doesn't know the difference between the visualization and the real thing," says Salitsky. "In visualization, the brain sends neural signals in the same patterns to the muscles, thus training them for the particular activity even though the muscles are not activated."

Science's role

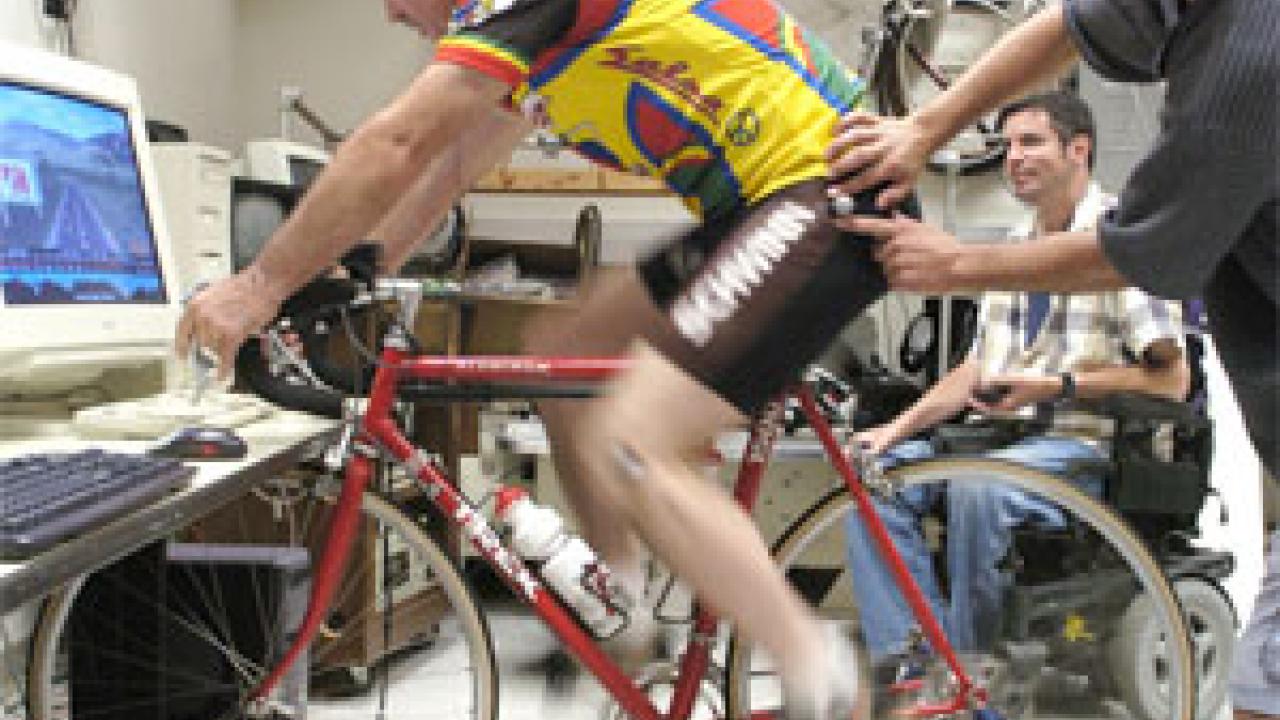

Science can help improve cycling performances, says Maury Hull, a biomechanical engineer who directs cycling-related research programs at the UC Davis Biomechanical Engineering in Sports Laboratory.

"Pedaling is an extremely repetitive action," says Hull, who has raced bicycles competitively for 20 years, "and research has shown that one in two cyclists will suffer knee injuries."

A cyclist will pedal about 50,000 revolutions in 125 miles — which is about equivalent to some of the Tour de France "stages," or one-day sections, Hull said. "Cyclists generate immense loads on their knees," he said. "The riders on the Tour de France are going 30 miles an hour on the flat stretches, and that kind of human-generated speed is mind-boggling."

To soften the impact on the knees, Hull's lab is studying cycling biomechanics and bicycle design. An example is a different type of "interface" between the pedal and the foot. Adjustments can be made, he says, similar to orthopedic devices designed to treat or adjust various biomechanical foot disorders.

Some of this research is making its way into the racing world. Hull attended the Tour de France in 1992 for a special scientific symposium on cycling.

Beyond the science, there is the spirit of the Tour de France. On the last day, the cyclists roll through the Champs-Ãlysées in Paris amid throngs of fans and TV cameras beaming the celebratory images to millions of viewers worldwide.

"It's like a dream," Heiden said. "It's inspiring."

Media Resources

Clifton B. Parker, Dateline, (530) 752-1932, cparker@ucdavis.edu