We began this series nearly a year ago, after another very hot summer. We end it in a changed world.

In some ways, the end brings us back to the beginning. By 2100, Sacramento is still expected to feel more like Phoenix or Tucson. That is still going to affect our lands, our health and our quality of life, especially for the most vulnerable among us. We still need solutions that both prevent future climate change and adapt to the changes already here.

In other ways, everything is completely different.

Triple threats

The triple threats of a global pandemic, racial injustice and rising temperatures are in our homes and on our streets, all at the same time. These issues are not academic; they are visceral. Heat is one area where health, climate change and racism build on each other and intertwine in ways that cannot be separated.

Let’s connect those dots: Fossil fuel combustion emits pollution and greenhouse gases, which fuel climate change. This raises global temperatures, translating to more intense droughts, wildfires and harmful smoke events for the Sacramento region.

The COVID-19 pandemic — itself due in part to environmental degradation — further affects people’s lungs and health. This makes those already struggling with underlying health conditions, such as asthma, respiratory diseases and diabetes, more vulnerable.

And the communities most at risk are disadvantaged communities, which centuries of systemic racism in the U.S. has ensured are primarily inhabited by people of color.

In California, only 17 percent of positive COVID-19 cases where racial/ethnic identity was known occurred in white people, as of late June. The remainder were people of color: about 55 percent Latino, 6 percent Asian, 4 percent Black, and 16 percent “other.” Recent national data from the CDC show that hospitalization rates for Indigenous and Black people are five times higher than for white people, and rates for Latinos are about four times higher than that of white people.

This isn’t just a vicious cycle, it’s a web of devastation.

There is no sure shot to fix it, no inoculation or vaccine that can bring us back to “normal” — as if normal is a place to which we should return. It’s millions of solutions working together not to go back to something, but to move forward into a better, more sustainable world we can all live with.

Sound idealistic? Perhaps. But summer 2020 has us in the middle of a heat wave, a pandemic, a recession and an invigorated uprising for racial justice — all at once. Inaction is not a valid option.

Months ago, we optimistically and temporarily named this final installment of Becoming Arizona “What Works.” Guess what? We don’t have all the solutions.

But there are ideas being voiced by public health, climate science and community leaders, written into climate action plans, and increasingly being viewed through the lens of a global pandemic and racial inequities.

Trees, essentially

When schools and parks shut down for the pandemic, many children and adults living in apartment complexes lost their access to greenspace and to the many health benefits trees provide.

“Trees are not just a matter of public health anymore but of emotional and behavioral health,” said Victoria Vasquez, the South Sacramento NeighborWoods organizer for the Sacramento Tree Foundation. “Where we live is exactly where we need those trees to be.”

That’s especially important for warming cities. Several studies have shown how a healthy tree canopy can make at least a 10-degree difference compared to shadeless neighborhoods. (We covered this in “Sacramento’s Urban Heat Island Divide.”)

Yet, since COVID-19 came to town, Vasquez has noticed a disturbing trend. There was a distinct drop in the number of tree requests by people in the disadvantaged community she serves.

“Most people we served in the past in South Sacramento are essential workers,” Vasquez said. “They are working at restaurants and daycare centers. They are struggling. So when their jobs are lost and they’re trying to feed their families, the last thing on their mind is, ‘I’m going to plant a tree today.’”

At the same time, there was a surge in requests from more affluent communities, which Vasquez attributes to more people in those neighborhoods working from home and taking the opportunity to improve their yards.

This micro trend illuminates the much broader issue — played out across several U.S. cities — of how heat, health, and racial disparities build on and exacerbate each other.

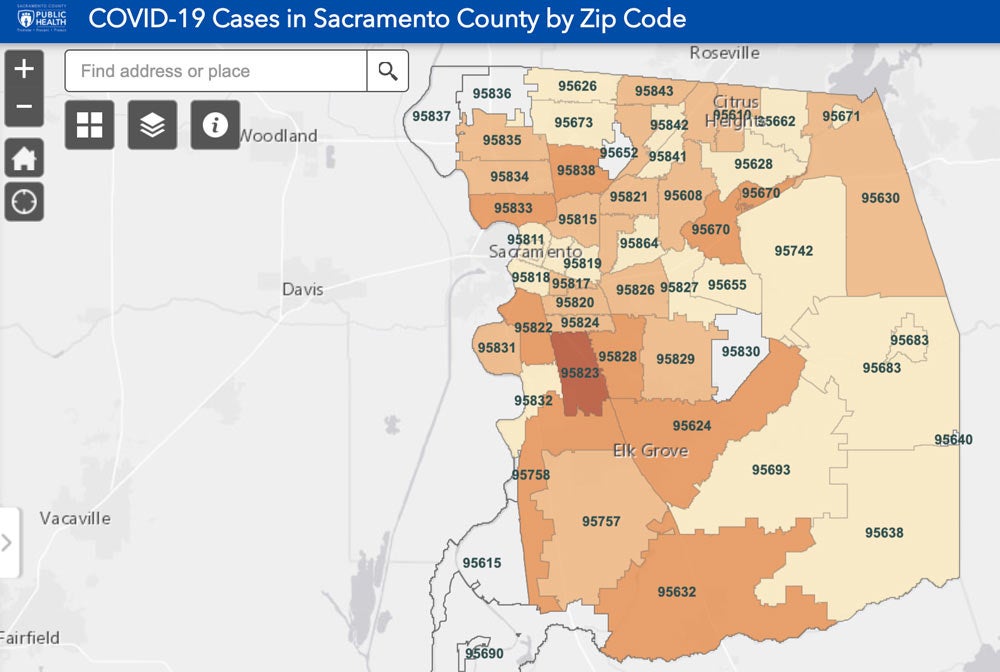

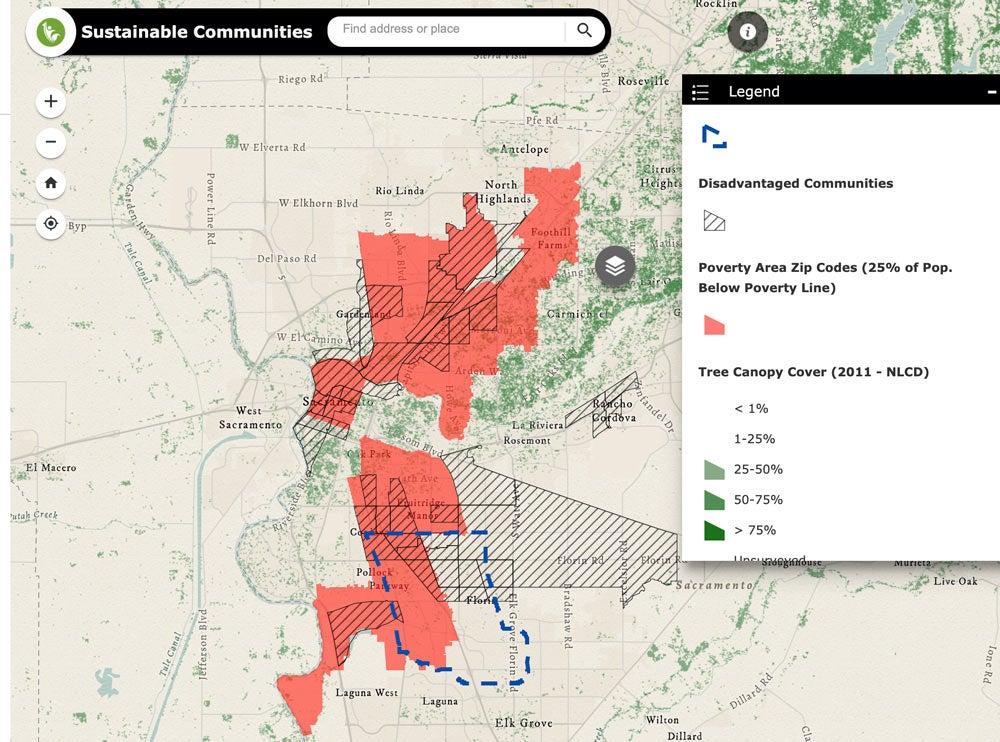

Underserved communities have among the highest rates of COVID-19 cases in Sacramento. If you layer city maps of COVID-19 cases, socioeconomically disadvantaged communities and tree canopy, the results are striking and sobering.

“You see so clearly that disadvantaged, unhealthy people don’t have as many trees in their neighborhoods, and they have higher, hotter temperatures,” Vasquez said. “It’s the perfect storm of environmental injustice. We’ve been preaching this a long time, and now it’s playing out in the worst-possible-case scenario. Hopefully, people will listen.”

COVID-19 complications

Meanwhile, it’s getting hotter and deadlier. Maricopa County, where Phoenix sits, already had four confirmed heat-related deaths as of late June this year, with 39 more under investigation. That’s up from the three deaths and 24 under investigation during the same time in 2019.

In Sacramento, as in Arizona, COVID-19 is complicating efforts to keep people cool:

- Many of our heat-relief go-to’s — beaches and public swimming pools, air conditioned malls and cooling centers — now pose their own threats and limitations.

- With unemployment on the rise, people may be disinclined to use their air conditioners or fix the one they have.

- While social connection is often one of the best defenses for senior citizens dealing with the heat, social distancing during the pandemic is limiting those in-person check-ins from friends and family members. (The Global Heat Health Information Network offers strategies on “Protecting Health from Hot Weather During COVID-19.”)

- And wildfire season is really just getting started. The state is already managing emergency evacuations and wildfire response in addition to all of the above.

You may be wondering, is this the part where we get to hear some solutions? Why yes, it is.

While the pandemic has laid bare our vulnerabilities, it’s also shown us what can be possible — from air quality improvements and conserving wildlife to reducing greenhouse gas emissions — if collectively we reduce our travel and slow down our lives.

“How do we take the best of what we’re learning today and think about how to systemize that?” asked Kate Gordon, director of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s Office of Planning and Research, during a virtual workshop of the Capital Region Climate Readiness Collaborative. “Like telework, telemedicine, and things like prisoners doing parole hearings by video rather than driving them all over the state. Every day we telework, we reduce our vehicle miles traveled. What can we learn from this massive and forced behavior change that can perhaps be longer lived?”

Undersung solutions

In the past 20 years or so that I’ve covered the environment, I’ve written hundreds of how-to-save-the-planet stories that talk about solutions like recycling, biking, climate-smart gardening, renewable energy, electric vehicles and energy efficiency. Those remain workable and important actions in the fight against climate change.

But increasingly, I’m hearing people talk about solutions that, even just a few months ago, many may have struggled to connect with climate change. Things like social diversity, affordable housing and health care are mentioned alongside electrification of cars and buildings, renewable energy and sustainable land use.

Even better, I’m seeing them actually written into local and regional climate action plans, such as the recently released Mayors’ Commission on Climate Change’s recommendations to achieve carbon zero by 2045 in Sacramento and West Sacramento.

‘A society in shock’

While 2020 has been a wake-up call for many about the intersections of health, climate change and social justice, Helene Margolis has been talking about and researching those connections for more than three decades, with the end goal of healthier, more resilient humans and environments. Margolis, featured earlier in this series, is an associate adjunct professor in the UC Davis School of Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine. I checked in with her again to see how her thoughts may have shifted since COVID-19 and the killing of George Floyd.

“We have a whole society in shock,” said Margolis. “How can we have resilience to these shocks — whether they’re climate shocks or COVID-19 shocks or the shocks from the murdering of innocent people? As horrible as the situation is, it’s brought to the surface a really raw wound. The hope is it isn’t just people of color saying this has to stop. I think there’s incredible opportunity in that. Both in the near term and longer term, we need to enhance our mental resilience for these shocks.”

She offers four areas of focus to help build that resilience:

1 ) Reimagine affordable housing. Safe, secure housing is central to being healthy, Margolis said. Studies have demonstrated health benefits of owning rather than renting a home, but home ownership isn’t feasible for everyone. Margolis is investigating sustainably designed, affordable housing developments where resident empowerment and social cohesion are fostered by community organizations. She wants to learn whether such developments can replicate the health benefits of home ownership. One model she mentions is powered by solar energy, has free wifi to address digital divides and offers a community electric car-share service.

2 ) Embrace telemedicine and affordable health care. Telemedicine is being used more than ever, and it represents a major opportunity to reach disadvantaged and more isolated populations, without the need for additional travel or exposure to others who are ill.

Also, making sure people have access to health care, particularly for those with chronic conditions, could diminish the impact of COVID-19 on people and communities, as well as lower both health and financial risks for individuals and society when wildfire smoke blankets the valley.

“You can have prevention of health impacts and prevention of climate impacts,” Margolis said. “By working together, you’re yielding co-benefits that translate into economic benefits.”

3 ) Get creative. The outdoors can offer immense health benefits. But how do we stay cool and socially distance? Parks from Manhattan to San Francisco are embracing creative and (dare we say) fun ways to socially distance through the use of lawn circles spaced six feet apart. Some describe them as “parking spaces for humans.”

4 ) A call for kindness and respect. For her final point, I will just quote Margolis in full:

“Another thing about racial disparities, or rather, racism — let’s call it what it is — it’s too easy to talk about disparities. At the core, our society is not leading with its heart. If you lead with your heart, it’s very hard to exclude people or diminish them.

“Somehow, we need to recognize that the racism and the horrible things that have happened to African Americans and Indigenous people is because people turned off one of the things that makes humans unique: the ability to choose to love, form attachments, and choose to modify their behavior to improve the society in which they live.”

She says the recent outpouring of support for the African American community by a broad cross-section of people is indicative of open hearts. But she adds that it is essential that is translated into long-lasting changes that bring a healthful, equitable future for all people.

“For that future to be realized, the societal changes must also reflect deep respect for the natural systems upon which all life depends,” Margolis said.

Relationship problems

When COVID-19 came on the scene, Kathryn Conlon, like many in her field, saw it as the embodiment of One Health — a concept in human health and veterinary sciences that recognizes the interconnected nature of humans, animals and the environment — and how important it is to protect built and natural spaces so we can protect ourselves.

She also saw how uprisings around racial injustices are exposing our troubled relationships with each other and the environment.

“You can’t talk about fixing climate change without addressing racial injustice, especially in the United States,” said Conlon, who specializes in climate adaptation health with UC Davis’ Department of Public Health Sciences and the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine.

That includes ensuring that people of diverse backgrounds are not only consulted about community climate-related actions, but that they also have a seat at the table. This marks a shift from mere buy-in to inclusion.

“Because there’s a sense of urgency around climate change, sometimes we forget that we need to make it a community solution,” Conlon said. “A sense of urgency isn’t license to give only certain voices the agency to make change. We’re going to need a diversity of thought, and we have to be able to talk to each other to do that.”

Adrienne Lawson, senior director for Health Equity, Diversity and Inclusion at UC Davis Health, said a lack of diversity can create unintended consequences and gaps, whether mapping out climate action plans or workforce development goals.

“We’re smarter when we have diverse perspectives,” she said. “A lot of time when people hear ‘diversity’ they wonder, ‘Will I lose my power, my position and prestige because I have to let you in my space?’ But it’s not really giving up something — you actually gain. Lifting up the entire community makes us more economically sound and healthier.”

“Nationally, African Americans are dying at higher rates from COVID-19 than any other group,” she said. “Why is that? It’s because many have underlying health conditions, like me now.”

As an African American woman, Lawson knew from previous studies that, despite being highly educated and financially stable, she could expect to have worse health outcomes than a poor white woman. Still, she was taken aback when she was recently diagnosed with pre-diabetes.

“I feel I have the economics and the education, but the mental and physical toll that racism has on people is very detrimental to your health,” Lawson said.

Lawson notices good things about the pandemic, as well: “We have a greater appreciation for people. Like if we can bring trailers to help the homeless within a week, why couldn’t we do that before? If we can give children in Oak Park and Meadowview laptops, why didn’t we do that before? If we can regularly provide food for kids and have all of these Black Lives Matter signs around, I don’t think we should stop. Now is the time to make significant changes.”

Recognize, reflect, act

So what can you do about all this? Conlon suggests first recognizing and reflecting on your own impacts on the environment and your community and then deciding which actions make most sense for you.

But individual actions only go so far. Civic engagement, “who we decide to give our power to” when we vote, and holding accountable those we vote into office are also important, she said. Engaging with policymakers doesn’t have to be contentious. Attending council meetings, responding to surveys and taking opportunities to provide constructive input help political leaders govern.

Large-scale movements, from Greta Thunberg’s climate strikes to Black Lives Matter, also hold the potential for major change, Conlon notes.

“I strongly believe we can find ways to adapt to extreme heat,” Conlon said. “There are going to be some communities that will experience extreme heat before others do. It’s up to us to decide sooner rather than later how to adapt and how we can make that an equitable transition.”

Lawson offers some final advice: “I just want to say, continue to be courageous. Marginalized people can’t do it on their own; they don’t have the power, or they wouldn’t be marginalized. The people who have the power need to bring everybody to the table and work on solutions together and be brave.”

The recap

Climate change, public health, and social and racial justice are intertwined. Solutions that can provide the most co-benefits — that lower emissions, improve health and address social and racial inequities — may be our best shot at a sustainable and resilient future, especially given reduced revenue sources. Individual actions can make a difference. Collective ones can, too. Start at home. Check in on your neighbors (from 6 feet away). Wear a mask. Don’t forget to vote. And be brave.

Hey, that was fun. Wanna do it again? Find the beginning of the five-part Becoming Arizona series at https://www.ucdavis.edu/climate/becoming-arizona.

Media contact(s):

Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-752-7704, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu

Media Resources

Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu

Read the rest of the Becoming Arizona Series:

- Part 1: This Arid Life - Preparing for 2100 Now and a Phoenix-Like Future in Sacramento

- Part 2: Lessons from Phoenix - What Sacramento Can Learn About Extreme Heat and Human Health

- Part 3: Sacramento's Urban Heat Island Divide

- Part 4: Cooling Sacramento - Low-Carbon Cooling in a Warming City