Coral reefs make up less than 1% of ocean habitat but are home to at least 25% of marine species. These incredibly biodiverse ecosystems are increasingly threatened by human actions, including anthropogenic climate change.

“Many people know that corals create habitat for fish and invertebrates, but corals also protect coastlines, because waves lose energy and weaken when they hit coral reefs,” said Rachael Bay, an associate professor in the Department of Evolution and Ecology at the University of California, Davis. “If coral reefs die and sea levels rise, coastlines will lose this protection.”

Though scientists have long known that corals vary in their ability to tolerate heat, it’s still unclear why some of the marine invertebrates cope better than others — even within the same species. To understand how genetics might help coral reefs adapt, Bay is undertaking a long-term field study in the Cook Islands in the South Pacific.

The project is a collaboration with Anya Brown, an assistant professor in the Department of Evolution and Ecology, who is investigating whether corals’ microbial communities might also help them cope with heat stress. Their findings could help coral conservation efforts in the Cook Islands and beyond.

“I’m interested in how coral microbiomes are changing with climate change, and whether heat-resistant and heat-susceptible corals have different microbial communities,” said Brown. “This project will help us determine whether there’s an individual microbe species or a collective adaptability that’s responsible for how a coral responds to temperature stress.”

How heat affects coral reefs

When corals become stressed, they discharge the symbiotic algae that nourish and color them, leaving them bleached and vulnerable. As global temperatures rise, these bleaching events are becoming increasingly frequent and severe. But while some corals die immediately during heat waves, others seem unbothered.

Though bleaching is associated with various environmental stressors including pollutants and changes in ocean acidity, rising ocean temperatures are the biggest single cause.

However, when a heat wave hits, not all corals are affected equally. “Individual corals respond to heat waves in really different ways,” said Bay. “You can have three corals of the same species right next to each other, and one will bleach and die, one will look totally fine, and the third one will bleach and then recover.”

Whether the corals survive higher temperatures could come down to their age, size, habitat, genetics and microbiome.

Coral genomes and microbiomes

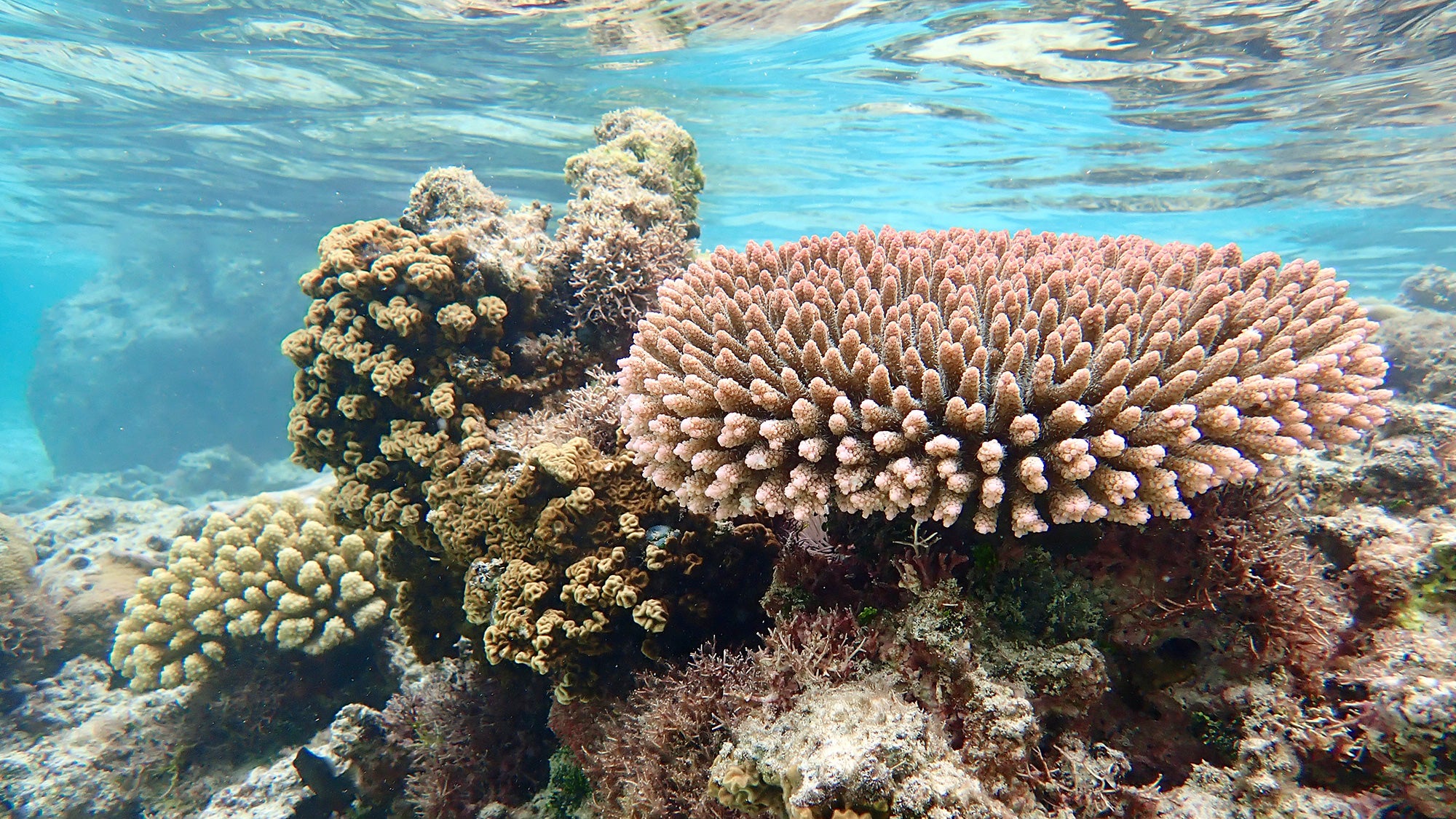

To zero in on the roles of genetics and microbes, Bay and Brown have established a coral nursery on Rarotonga, the largest of the Cook Islands. Formed by volcanic activity, the 15 islands are encircled by some of the most vibrant coral reefs on Earth, which support organisms including sea cucumbers, sea stars, clams, reef sharks, rays and turtles.

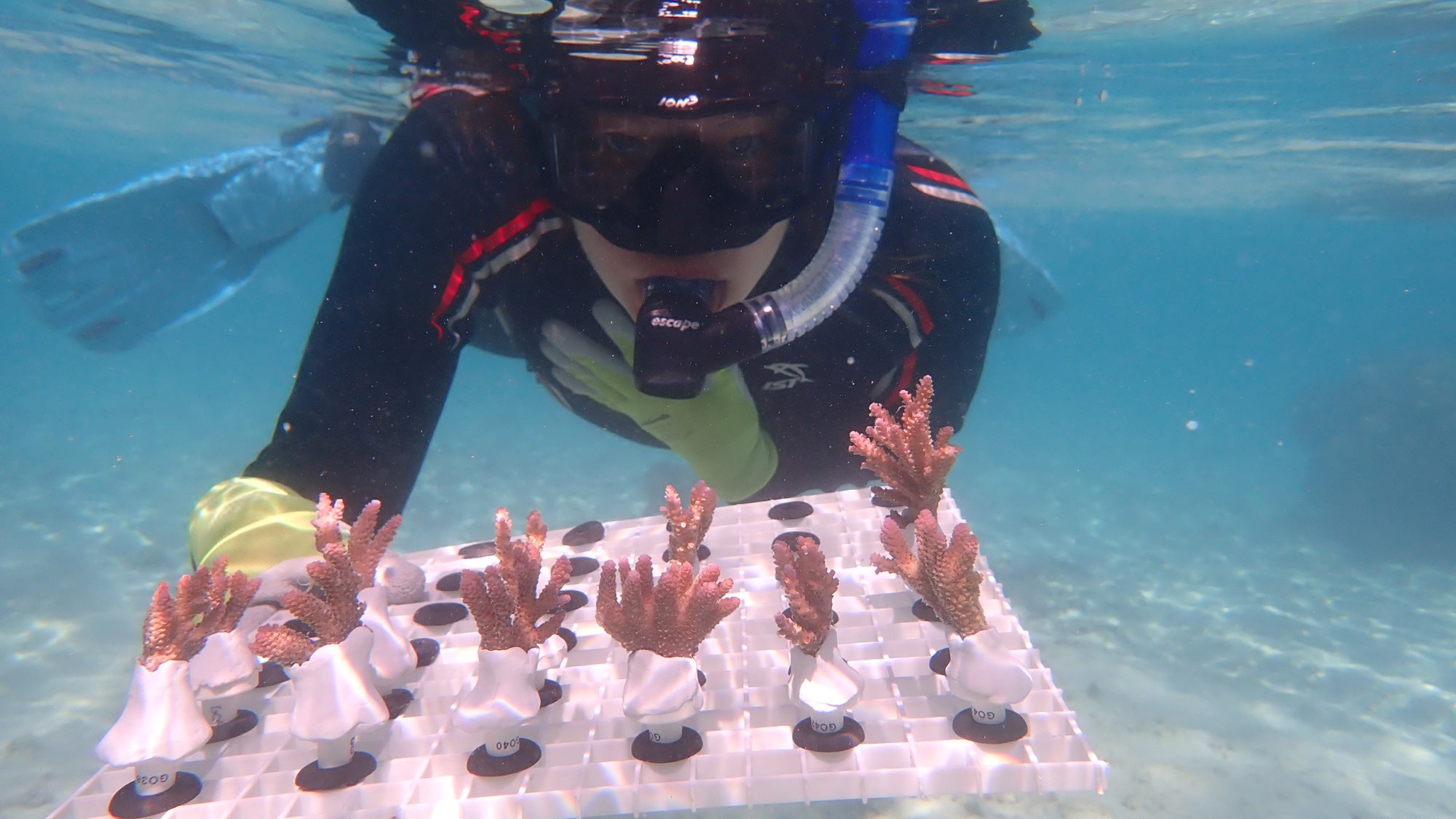

By planting similarly sized pieces of coral in the same location, the UC Davis researchers and their partners will be able to assess how genetically and microbially different corals fare when exposed to identical conditions.

“The nursery puts the corals on an even playing field so that we can understand the mechanisms behind why different corals respond differently to temperature stress,” said Brown. “Because Rachael and I are tackling similar questions from different angles, we'll be able to answer questions about whether and how the coral’s microbiome and host genome interact.”

The project generates large amounts of genomic data, which the researchers analyze on campus with help from the UC Davis Genome Center and the High-Performance Computing Core Facility.

Building a coral nursery

Bay and Brown began building the nursery in 2024 with funding from National Geographic and a UC Davis Global Studies Seed Grant. Last summer, their team returned to add hundreds of new coral specimens to the nursery.

“A large part of the initial field work involves snorkeling around looking for corals,” said Bay. “We have one particular species that we’re focusing on for this project, called Acropora hyacinthus, and sometimes they’re hard to find; sometimes they’re all we find!”

When they find a suitable coral, the researchers break off a small, thumb-sized portion to plant in the experimental nursery. Because corals are clonal, these fragments grow into a new individual that is genetically identical to the original colony. During heatwaves, which usually begin in February and March, local collaborators from the Cook Island’s nonprofit organization Kōrero O Te ‘Ōrau monitor the corals to see how they fare.

“This project will also help identify heat-tolerant corals for use in local restoration efforts,” said Bay. “One thing we don’t know yet is whether corals that recover from one bleaching event are better able to tolerate future heat waves.”

Collaboration in reef restoration research

Bay and Brown’s collaboration with Kōrero O Te ‘Ōrau is essential for their research on Rarotonga. The nonprofit, whose name translates to “knowledge of the land, sky and sea,” aims to foster environmental stewardship and advance traditional knowledge.

“Our partners at Kōrero are our people on the ground when we’re back on campus,” said Bay. “They also hold the local knowledge that shapes some of the questions we ask through our research, which really helps us think about the reefs in Rarotonga in a deeper way.”

The benefits go both ways: Bay and Brown’s research yields valuable information that informs local reef restoration efforts and provides opportunities for Kōrero’s young environmental stewards to participate in meaningful field research.

“Our collaboration with UC Davis provides a unique opportunity for the young people in our program to work alongside experienced researchers, inspiring some to pursue a career in marine science,” said Teina Rongo, chairman and cofounder of Kōrero, who holds a Ph.D. in marine biology. “With the ocean playing such a vital role in our lives, it’s essential that we have more local professionals trained in this field, enabling us to become better stewards of our marine resources.”

Rapid evolution and conservation

Though we often think of evolution as a slow process, it can occur very quickly. “Rapid evolution” is usually spurred by sudden or dramatic environmental changes, as is the case with climate change.

“We now know that evolution can happen rapidly — and even immediately in some cases — which means that people can affect evolution on human timescales,” said Bay. “If we can understand how that’s happening, we could predict how populations will look in the future.”

Shifting microbiomes could help corals adapt even more quickly to climate change. “While coral populations may take a long time to evolve or adapt, its bacterial communities can change on much faster timescales, which might play a role in protecting coral from future heat stress,” said Brown.

This information could help conservationists decide where to allocate resources.

“Some populations might be able to adapt to environmental change more effectively than others,” said Bay. “For a conservation manager deciding which populations to conserve, this is one of many pieces of information that could help — do I want to conserve the population that’s more likely to adapt in the future, or do I want to give some extra protection to the population that’s a little bit more vulnerable so that it might persist?”

Bay’s research has been funded by a National Science Foundation (NSF) Career Grant and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. Brown’s research has been funded by National Geographic and a UC Davis Global Studies Seed Grant. This project has utilized several UC Davis research core facilities, including UC Davis Genome Center and the High-Performance Computing Core Facility.