Dogs 10 years and older have a 50% chance of dying from cancer. They also develop the same types of cancers that humans do because their immune system is closely related to ours. Now human oncologists are studying cancer in canines in the hopes of benefiting both animals and humans. In this episode of Unfold, you’ll learn how UC Davis veterinarians and physicians are collaborating to help human cancer patients and their furry best friends.

In this episode:

Robert Canter, surgical oncologist with UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center

Michael Kent, radiation oncologist and director of the UC Davis Center for Companion Animal Health, School of Veterinary Medicine

Danae Unti, owner of Boone, a dog who completed a cancer clinical trial

Transcript

Transcriptions may contain errors.

Amy Quinton

Hey, Marianne, there's a picture of a dog named Boone that was sent to me that I want to tell you about.

Marianne Russ Sharp

What kind of dog is Boone?

Amy Quinton

Well, it's hard to say. He's a big dog.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Big is not a breed Amy.

Amy Quinton

Yeah, I had to ask Boone's mom, human mom, about his breed because what do I know about dogs?

Marianne Russ Sharp

Really? All you need to know is dogs are great. Who's Boone's mom, by the way?

Amy Quinton

Her name is Danae Unti. She told me that figuring out Boone's breed was a bit of a puzzle. She was led to believe that Boone and his brother Wayland were greater Swiss mountain dog mixes, but she found out later she was misinformed.

Danae Unti

They did not have any Swiss mountain dog. It was mostly you know, retriever and rottweiler and a couple couple of fun other things. Booney he sort of looked like a mix of like a an Irish setter and, and a really like dark golden retriever almost with some with some rottweiler coloring.

Marianne Russ Sharp

So Boone's a mutt.

Amy Quinton

Boone's a mutt. And in this photo taken when he was about eight, he's sitting on the seat of a boat with beautiful Lake Sonoma in the background, and his eyes are kind of closed and he's clearly just soaking in the California sun.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Having the time of his doggy life?

Amy Quinton

His doggy life. Yeah, it looks like all he needs is a nice glass of Unti wine and he'd be set.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Wait Unti. Hang on, Unti the winery?

Amy Quinton

Yeah, Boone belong to the Untis.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Or maybe the Untis belonged to Boone? At least I know how it works in my family. Okay, so why are we hearing about Boone in the first place?

Amy Quinton

I mean, why not? You just said dogs are great.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Okay, True. True.

Amy Quinton

Well, one day several years ago, Danae and her husband who live in Sonoma County, were packing up the car and about to head out for a day at Tomales Bay with Boone, of course,

Marianne Russ Sharp

Nice.

Amy Quinton

When Danae says she noticed something about Boone.

Danae Unti

I remember leaning over and grabbing Boone's head and feeling his jaw as I as I grabbed his head and kissed his face. And I could feel that there was swelling on the right side of his jaw that I had not noticed before. I basically just opened his mouth and he yelped a little bit and I could see that there was a mass on the top of his jaw.

Marianne Russ Sharp

A mass. Oh no.

Amy Quinton

Yeah. Oh, no. The mass turned out to be cancer, an oral melanoma that was inoperable. And this news came at a time when they just lost Boone's brother Waylon to cancer.

Danae Unti

It was devastating. Um, you know, my, my animals are my whole life. And, you know, we love them dearly. Losing Waylon was a real was a real loss. And it felt you know, we felt so lucky and and just so fortunate to have Boonie with us and really hoped for a couple more years. Yeah. How old was Boone?

Amy Quinton

He was eight at the time of diagnosis.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Yeah, big dogs like that often don't live as long as smaller dogs, but you'd still expect and really want more time.

Amy Quinton

Yeah, but did you know about one in every four dogs will develop cancer?

Marianne Russ Sharp

No, I did not know it was that common? Okay, Amy, this is turning out to be a really awful story.

Amy Quinton

It's not awful. It's hopeful, actually. You see, Danae's vet told her about a clinical trial at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine that would test a new cancer treatment. It's part of our comparative oncology program.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Oh, right. This is the program between the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine and the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center. It looks at what companion animals both dogs and cats can teach us about cancer in humans.

Amy Quinton

And the other way around, so both humans and animals benefit.

Marianne Russ Sharp

What I want to know is did Boone benefit? Did the treatment work?

Amy Quinton

You'll find out. Coming to you from UC Davis

Marianne Russ Sharp

and UC Davis Health,

Amy Quinton

this is unfold a podcast that breaks down complicated problems and unfolds curiosity driven research. I'm Amy Quinton.

Marianne Russ Sharp

And I'm Marianne Russ Sharp.

Amy Quinton

So Marianne, I visited the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Wait, don't you always visit the vet school?

Amy Quinton

Well I have been there a lot. I do like animals but I had the chance to visit Dr. Michael Kent, a radiation oncologist who co directs the comparative oncology program.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Oh the comparative oncology program is pretty unique. Only a few institutions nationwide offer such a program.

Amy Quinton

Before we get into the details of the program. We're going to start first with understanding a little about cancer in dogs. Kent takes me down a long hallway at the Center for Companion Animal Health. Hundreds of framed photos of dogs and cats line one of the walls.

Michael Kent

Oh patients yeah, these are some of my patients over the years and some of the other doctors' patients over the years. It's a nice wall. Reminds me what we do.

Amy Quinton

Kent says he's treated thousands of patients over his career here, too many to count. The oncology department averages a few thousand animals each year with cancer. Many of them dogs.

Michael Kent

Half of all dogs that live till 10 will die of cancer. You know, about 25% of dogs will develop cancer, it's a little less for cats. And you know, so cancer still is a major problem in the species and, you know, as dogs age and live longer because they have good nutrition, they have vaccines, so they don't die of infectious diseases. They live long enough to develop cancer.

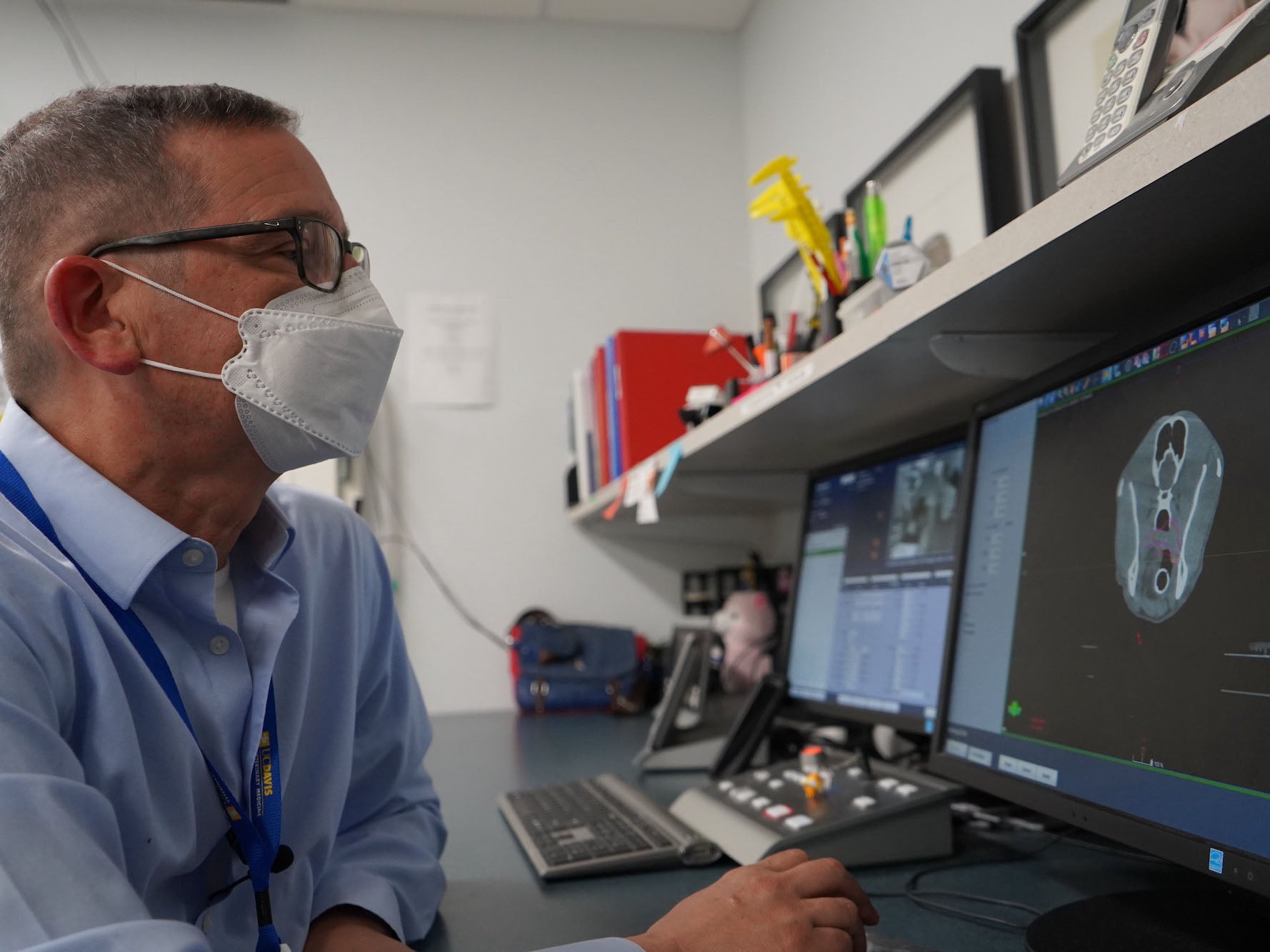

Amy Quinton

We continue our trek into a room that holds a huge machine called a linear accelerator. It looks a lot like a giant microscope, a dog is placed on a movable exam table underneath the device. The machine uses radiation therapy to target the cancer with pinpoint accuracy. Vet tech Sarah Stephens preps a dog a German Shepherd mix for treatment.

Sarah Stephens

I'm going to move her up a little bit.

Amy Quinton

The dog has a cancerous tumor in her pelvis that is now just microscopic. Kent conducts clinical trials and uses high-tech equipment like this one, with one goal, to offer the best treatment for animals with cancer. Ken says dogs get all the same cancers that humans get.

Michael Kent

You know when we think about it. You know dogs get brain tumors likely gliomas and glioblastomas dogs get bone tumors like osteosarcoma. Dogs get melanomas they're more commonly going to be in their mouth that they do get skin ones though they don't tend to have the same causes and biology because it's not from being out in the sun too much.

Amy Quinton

The list is long. Kent says over the years veterinarians have had to use what they've learned about fighting cancer in humans to fight cancer in dogs.

Michael Kent

You know, initially when I became a veterinarian oncologist, you know, they didn't make linear accelerators for medical therapy for dogs or cats or horses. They made it for people. And so we took what we knew in humans and brought it back to our patients.

Amy Quinton

But the comparative oncology program is changing that.

Michael Kent

The idea now is also be able to flip that paradigm and take what we learned in those same companion species like, you know, our dogs and cats that live with us and apply it to humans.

Amy Quinton

Marianne the idea of comparative medicine isn't new, of course, scientists have long used creatures like rats and mice to research cancer treatments and drug therapies.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Right, but there are limitations to that. Dr. Robert Cantor co- directs the comparative oncology program at the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center. He says the most notable difference is that cancers and rats and mice are not naturally occurring.

Robert Canter

In mice, it's it's a question of us implanting cancer, or manipulating the genes of mice. So they develop cancers or, you know, exposing them to things that are very, very damaging, so they develop cancer. And that obviously serves a purpose to evaluate that and study it. But it's really not the same cancer that humans and dogs get. And therefore, you know, may fall short, in translating what we learned in mice into people.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Manipulating these genes in mice can also disrupt the immune system, making it difficult to know how a tumor would actually respond to a therapy. Canter also says it's really easy to cure cancer in mice, compared to humans or dogs.

Robert Canter

And because of that are related to that almost all drugs, that statistic we sort of teach people is about 90% of drugs that actually move from mouse studies to human studies fail. And so there really is a large failure rate. And again, that is something where I think the dog cancer model can can provide benefit.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Unlike mice, dogs respond to cancer therapies in the same way as humans, so they can help identify drugs or treatments that are more effective, and they can identify drugs that are going to fail in humans a lot sooner.

Amy Quinton

And Kent says dogs can develop cancer in the same way as humans, because they're vulnerable to the same things we are including bad air or environmental toxins.

Michael Kent

My dog, for example, my dogs with me 24 hours a day. Dog is exposed to everything I'm exposed to has similar exercise times, you know, that I have. And so really, when you look at it, they've co evolved with us for over 10,000 years. And their biology is very similar to ours. Even their immune systems are very similar to ours.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Dogs even have similar microbiomes you know, all those microbes and bacteria that naturally live on us. That's because dogs pretty much eat what we eat. I mean, I'm not eating kibble, but you know what I mean? There are differences of course, and another major one, of course is that dogs age faster,

Amy Quinton

But that that can be a benefit in some ways, especially if you're trying to understand how long a treatment may work. As an example, Kent says the goal of a clinical trial going on here at the vet school is to develop a vaccine against cancer in dogs that might eventually translate to humans.

Michael Kent

You know, if you vaccinate a few 100 dogs and follow them forward, that's much easier. In a sense to do than vaccinating people and following them their whole lives.

Robert Canter

You can evaluate and get results more quickly in dogs than you can in people.

Amy Quinton

That's cancer. He agrees that working with dogs has its advantages.

Robert Canter

Part of that too, is just the steps involved to get a trial open in people with regulatory issues and financial issues and recruitment issues. human trials can can be very lengthy and very resource intensive, which slows the process.

Marianne Russ Sharp

The comparative oncology program has had success stories, including new ways to treat cancer in dogs. Canter says they have developed treatments that have either translated to humans or are in the beginning stages of human trials.

Robert Canter

We did the first clinical trial with natural killer cells in dogs.

Amy Quinton

Natural killer cells are a group of cells in your body that are part of the immune system and can fight cancer cells.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Just recently, doctors and veterinarians also developed a treatment for lung cancer that has shown promise.

Robert Canter

We've also done a trial with an inhaled immunotherapy called Interleukin 15. And we've had some very exciting I mean, in, in our opinion, some very exciting results in terms of dogs having significant benefits from the inhaled immunotherapy causing regression of tumors metastasis in the lungs.

Amy Quinton

This particular immunotherapy, which is a way to harness a patient's own immune system to kill cancer, had never been given as an inhaled treatment on a dog or human.

Marianne Russ Sharp

But oncologists found the method reduces toxicity exposure to the rest of the body. So the goal is to eventually start a human trial.

Amy Quinton

All of these success stories would not be possible without the help of dog owners, like Danae Unti, you know, Boone's mom, who we talked about at the beginning of this story.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Yes, please do get back to Boone's story. I've been dying to know what happened.

Amy Quinton

Well, Boone had oral melanoma, which can be extremely invasive. Danae found out that even with chemotherapy and radiation, few dogs are cured and many times the cancer comes back.

Marianne Russ Sharp

But then she found out about the clinical trial, right?

Amy Quinton

A clinical trial was designed to assess a drug called Zox. The hope was it would make tumors like Boone's more susceptible to radiation therapy and help the immune system attack the tumor.

Marianne Russ Sharp

So she decided to go through with a trial for Boone.

Amy Quinton

Yeah, but it was a decision Danae says they weighed carefully.

Danae Unti

People think that you are extending your dog's life and for selfish reasons, and that you're putting your animal perhaps through discomfort in the name of science, or just in the name of your own selfish needs. And I just, that really just couldn't be further from the truth.

Amy Quinton

She says if she had a dog, which she does now, who gets anxious or nervous around strangers in strange settings, she likely wouldn't do the same. It might be too stressful for him.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Yeah, because I can imagine it's a lot of trips to the vet.

Amy Quinton

Right, but she says Boone just wasn't that kind of dog.

Danae Unti

Boone, like thought he was going to a health spa. I mean, he had the most fantastic times going, he would jump out of my car when we arrived and he was like, mom drop me off close to the hospital. I'm gonna go see my friends like he was he was a superstar there. And you know, and that that was part of it to.

Amy Quinton

He was a superstar there!

Marianne Russ Sharp

That's hysterical. So I think he's the perfect candidate. So did the drug work did Boone's cancer go away? This is the real question. We want to know Amy.

Amy Quinton

Well, after given Zox Boone had four weekly rounds of radiation therapy in the linear accelerator we told you about earlier. And after the fourth round, his tumor had shrunk. And two weeks later, there was no visible tumor.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Yes, that's amazing. That's what Danae said.

Danae Unti

It was really amazing. And it was really nothing we ever expected going into it. So it was it was it was just like it was a dream. You know, it was just all we could have imagined and hoped and dreamed for him.

Amy Quinton

Marianne, I told you Boone got his diagnosis when he was eight, he lived almost another five years, he was almost 13 when he passed away,

Marianne Russ Sharp

Oh, that's great for a big dog. Such a happy story.

Amy Quinton

And while not every clinical trial results in so much success, Danae had this to say about her experience.

Danae Unti

UC Davis wouldn't have allowed me to push for things that weren't in Boone's best interest, you know, everything was for the quality of life of Boone, and in his best interest, and it was just a cherry on top that we were getting research that was going to help, you know, humans down the line. So it just it really was this win win situation all around in, in our case.

Marianne Russ Sharp

So is the drug going to help humans? Have they started clinical trials?

Amy Quinton

Kent told me the drug is still in development. It started the first human trial for safety, but has not yet been given to cancer patients.

Marianne Russ Sharp

But that's the hope?

Amy Quinton

Kent says the goal of the comparative oncology program is actually broader when you think about it.

Michael Kent

What's really nice is that we have the structure within the cancer center to actually do these types of trials to bring people together who work in different types of research in different species in order to pursue the one goal I mean, it's ending cancer. It's not ending cancer in people it's not ending cancer in dogs or ending it's ending cancer.

Marianne Russ Sharp

That's the perfect way to end this episode.

Amy Quinton

And you can find that photo of Boone on the boat that we talked about in this episode on our website, and you can find more episodes of Unfold at ucdavis.edu/unfold. I'm Amy Quinton.

Marianne Russ Sharp

And I'm Marianne Russ Sharp.

Amy Quinton

Unfold as a production of UC Davis original music for Unfold comes from Damien Verrett and Curtis Jerome Haynes. Additional music comes from Blue Dot Sessions. If you liked this podcast check out UC Davis's other podcast, The Backdrop. It's a monthly interview program featuring conversations with UC Davis scholars and researchers working in the social sciences, humanities, arts and culture. Hosted by public radio veteran Soterios Johnson. The conversations feature new work and expertise on a trending topic in the news. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

Marianne Russ Sharp

You can now listen to unfold on your smart speaker. Just ask Echo to "Play Unfold podcast for me" or ask your Google Home, it's that thing that looks like an air freshener sitting on your shelf, or subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.