Biomedical engineers at the University of California, Davis, are cracking the code of the body’s message system.

Extracellular vesicles, or EVs, are tiny biological bubbles that carry nucleic acids and proteins between cells, playing an essential role in tissue repair, neuroprotection and immune health. By isolating the surface proteins of these bubbles, researchers can understand more about their biology and build tools to transform extracellular vesicles into next-generation drugs for cancer and other diseases. The findings are detailed in a paper published in ACS Nano.

“EV-mediated intercellular communication is a very powerful system that controls many physiological and pathophysiological phenomena,” said Aijun Wang, a corresponding author of the new paper and professor of biomedical engineering and surgery. “We know that EVs are therapeutically useful. But how do we define what dictates their functions?”

Currently, EV surface proteins are like words lost in translation. They’re perceivable, they carry meaning, but what each one means and how it changes the significance of the sentence (or, EV) is unclear.

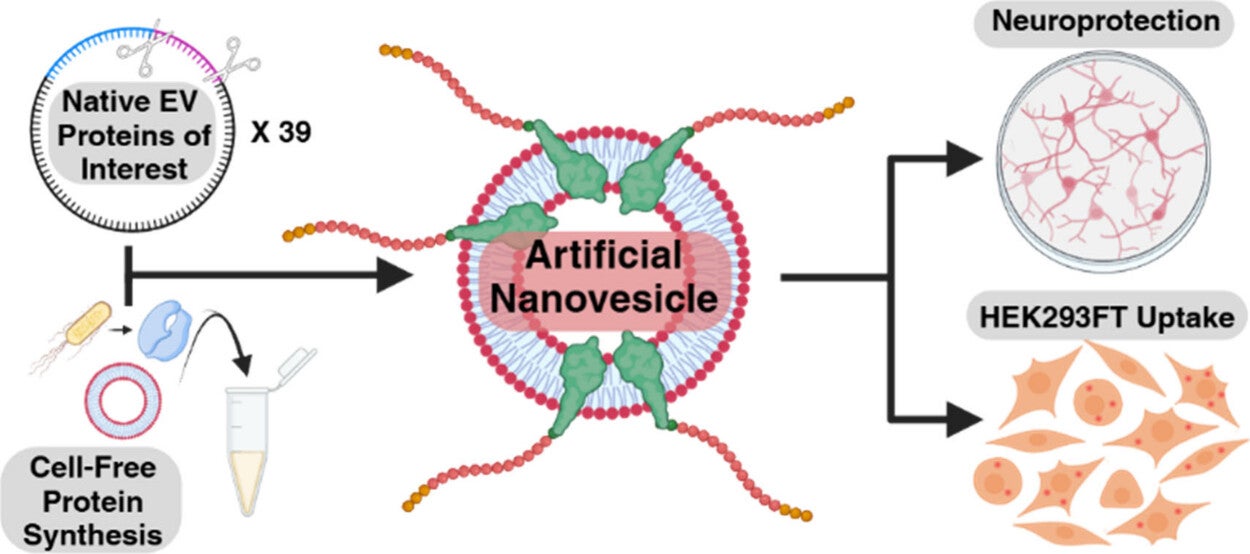

The UC Davis team’s Vesicle Engineering Systems using Synthetic Expression and Loading system, or VESSEL, will allow researchers to probe protein function and create something like a biological dictionary for EVs. It creates a particle with only one EV surface protein, enabling researchers to test its specific role in isolation.

Cell-free systems to make synthetic proteins

The system uses cell-free systems as the basis for producing synthetic EV surface proteins. This approach is notable for its ability to produce proteins rapidly and is widely used as a biological factory throughout academia and industry, making VESSEL an accessible and scalable platform for others to investigate EV surface proteins.

“The design of the system really makes it generalizable, meaning, if you have a cell-free system, then you can already go and make EV surface proteins,” said Cheemeng Tan, a corresponding author on the paper and professor of biomedical engineering.

In the paper, Tanner Henson, first-author on the paper and a biomedical engineering Ph.D. student co-mentored by Wang and Tan, used VESSEL to profile the protein distribution of EVs derived from mesenchymal stem cells, notable for their regenerative properties. One of the significant findings was that the CADM1 protein, previously unreferenced in medical literature, shows promise for ensuring vesicle intake by cells.

While more research is needed, findings like this point toward a future where biomedical engineers can create next-generation therapeutics with engineered EVs. By knowing which proteins serve which functions, researchers can build EVs for specific purposes like LEGO.

“[VESSEL] will enable us to understand EV-based therapeutics more deeply and much more tangibly than ever before,” Henson said. “Translation: that's a bigger picture. We're moving towards various translational applications of VESSEL, especially in treating neurological disorders.”

The research was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering.

Media Resources

Prototyping Minimal Extracellular Vesicle Mimetics Using Cell-Free Synthesis (ACS Nano)

Matt Marcure is a content specialist with the UC Davis College of Engineering, where this article was originally published.

More news from the UC Davis College of Engineering