By tracking swarms of very small earthquakes, seismologists are getting a new picture of the complex region where the San Andreas fault meets the Cascadia subduction zone, an area that could give rise to devastating major earthquakes. The work, by researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey, the University of California, Davis, and the University of Colorado Boulder, is published Jan. 15 in Science.

“If we don’t understand the underlying tectonic processes, it’s hard to predict the seismic hazard,” said co-author Amanda Thomas, professor of earth and planetary sciences at UC Davis.

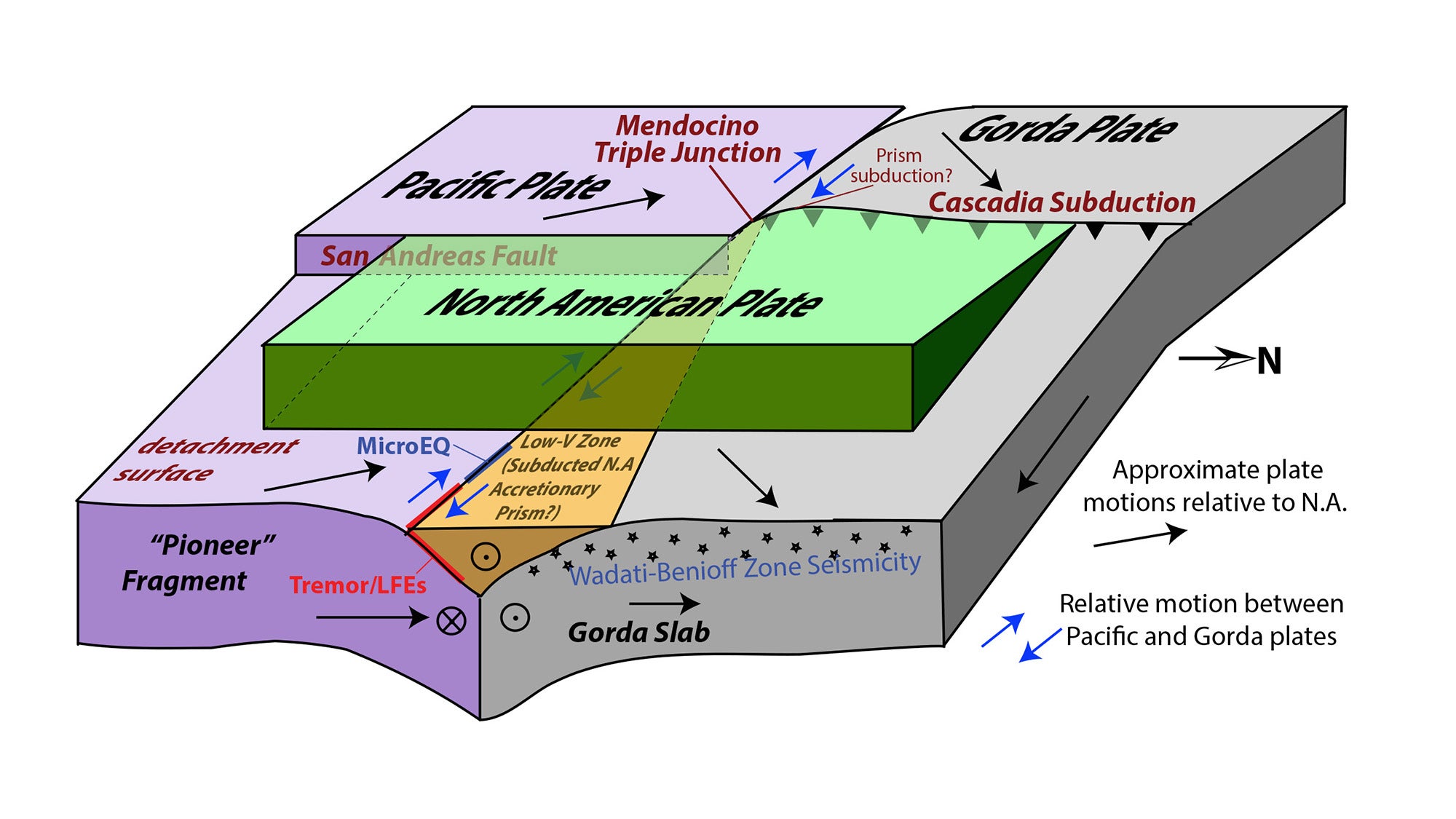

Three of the great tectonic plates that make up the Earth’s crust meet at the Mendocino Triple Junction, off the Humboldt County coast. South of the junction, the Pacific plate is moving roughly northwest against the North American plate, forming the San Andreas fault. To the north, the Gorda (or Juan de Fuca) plate is moving northeast to dive under the North American plate and disappear into the Earth’s mantle, a process called subduction.

But whatever is going on at the Mendocino Triple Junction is clearly a lot more complex than three lines on a map. For example, a large (magnitude 7.2) earthquake in 1992 occurred at a much shallower depth than expected.

First author David Shelly of the USGS Geologic Hazards Center in Golden, Colo., compared it to studying an iceberg.

“You can see a bit at the surface, but you have to figure out what is the configuration underneath,” Shelly said.

Shelly, Thomas, Kathryn Materna at CU Boulder and Robert Skoumal at USGS’s Earthquake Science Center at Moffett Field, Calif., used a network of seismometers in the Pacific Northwest to measure very small, “low-frequency” earthquakes occurring where the plates rub against or over each other. These earthquakes are thousands of times less intense than any shaking we could feel at the surface.

They confirmed their model by looking at how the plates respond to tidal forces. The gravitational forces of the Sun and Moon pull on tectonic plates just as they do on the waters of the ocean. When tidal forces align with the direction in which a plate wants to move, you should see more small earthquakes, Thomas said.

Five moving pieces

The new model includes five moving pieces, not just three plates — and two of them are out of sight from the Earth’s surface.

At the southern end of the Cascadia subduction zone, a chunk has broken off the North American plate and is being pulled down with the Gorda plate as it sinks under North America, the team found.

South of the triple junction, the Pacific plate is dragging a blob of rock called the Pioneer fragment underneath the North American plate as it moves northwards. The fault boundary between the Pioneer fragment and the North American plate is essentially horizontal and not visible from the surface at all.

The Pioneer fragment was originally part of the Farallon plate, an ancient tectonic plate that once ran along the coast of California but is now mostly gone.

The new model explains the shallowness of the 1992 earthquake, because the subducting surface is shallower than previously thought, Materna said.

“It had been assumed that faults follow the leading edge of the subducting slab, but this example deviates from that,” Materna said. “The plate boundary seems not to be where we thought it was.”

The work was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

Media Resources

Low-frequency earthquakes track the motion of a captured slab fragment (Science)

Media Contacts

- Amanda Thomas, UC Davis Earth and Planetary Sciences, amthom@ucdavis.edu

- David Shelly, U.S. Geological Survey, dshelly@usgs.gov

- Andy Fell, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-304-8888, ahfell@ucdavis.edu