While the wettest storm season in California’s recorded history crushed roofs and swelled snowbanks in the Sierra Nevada, the state’s coastal communities suffered plenty of their own losses. The casualties included waterside businesses swamped by storm surges, fishing piers smashed by rising seas, and coastal roads collapsed by debris flows.

What’s worse, the extreme weather California experienced during the winter of 2022–23 is likely to become more common due to climate change. This means the hundreds of coastal communities situated along California’s coast will need to grapple with decades of climate-induced woes. These will include erosion from sea level rise, marine heat waves, harmful algal blooms, and declines in water quality due to flooding.

Knowing when to expect events like these could help coastal communities brace for serious consequences. Officials could have a better sense of when to encourage sandbagging of buildings, or where to call for evacuations. A new project will help coastal communities forecast climate change impacts by utilizing long-term records of coastal and estuarine data from the UC Natural Reserve System and other monitoring sites.

Led by UC scientists, the project will make use of decades of climate, ocean, and estuary data from nine NRS reserves and nearby monitoring sites. The researchers will gather the information from disparate databases, analyze it for patterns, identify new ways to forecast potential problems, and deliver warnings and other actionable information to government agencies and community leaders.

“This project pulls together everything that people have been tracking over a long period of time to ask questions about how climate is changing and has changed,” said Eric Palkovacs, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz and a principal investigator on the project. “Because we have monitoring at these sentinel sites, and we can relate the conditions at these sites to conditions nearby, we can help communities be prepared.”

“All people should value these long-term data sets more than they have," said John Largier, a professor of coastal oceanography at UC Davis and director of its Bodega Marine Laboratory. "This project will be an example of what these data sets can do for us.”

Additional principal investigators on the project are Sarah Giddings, a professor of physical oceanography at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, and Andy Brooks, director of the NRS’s Carpinteria Salt Marsh Reserve.

A network of coastal reserves

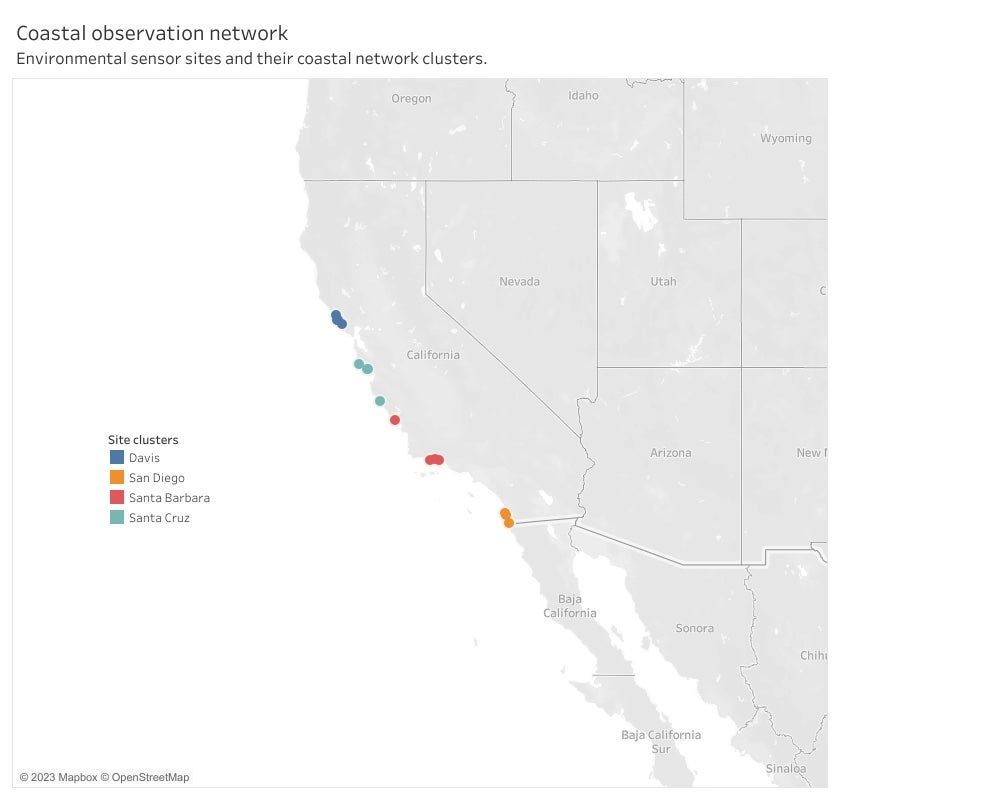

The project will establish a network of 15 monitoring sites across a 500-mile length of California coast ranging from Sonoma County south to San Diego County. This stretch coincides with the locations of California’s most populous coastal communities.

The network is divided into four geographic clusters. Each cluster includes at least one coastal and one estuary site, as well as NRS and non-NRS sites. A single UC campus manages the NRS reserves in each cluster.

The coastal monitoring network contains four clusters, each of which includes both coastal and estuary locations. NRS reserves are indicated in italics.

At each NRS reserve, climate stations have been tracking conditions such as air temperature, windspeed and direction, and precipitation. Additional sensors have been measuring factors such as seawater temperature, water pH, chlorophyll levels, water levels, and water quality.

Spotting trends

Records of environmental conditions go back decades at each monitoring site. In the case of the NRS’s Scripps Coastal Reserve, daily records of water temperature date back more than a century to 1916.

“These data help us put a finger on the pulse of the ocean,” Largier said.

The parallels between human vital signs and ocean health can be extended even further, Largier says. Just as tracking a person’s pulse continuously over time reveals far more than a one-time measurement, monitoring coastal and ocean conditions over many years is far more valuable than a snapshot here and there.

“This project can tell us the equivalent of what the ocean’s typical heartbeat is,” Largier said. Once what’s “normal” for each measurement has been identified, “then you can start identifying anomalies, and when and why those anomalies are occurring.”

“These data help us put a finger on the pulse of the ocean.” — John Largier, UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory

These patterns should provide answers to a bevy of additional questions. These include whether marine heat waves are occurring off California more frequently, or whether they are stronger or more prolonged; whether the wind is blowing harder than it used to; and whether one condition, such as stronger winds, might be associated with another condition, such as colder water temperatures.

Such associations could help scientists provide information communities can use to improve public safety or reduce damage to infrastructure as well as to steward natural lands and aquatic ecosystems.

“If we can come up with meaningful indices, we can package that information and deliver it to local governments,” Largier said.

For example, as rain and runoff fill the NRS’s Younger Lagoon Reserve, water level at the site might be a good indicator of flood risk along the San Lorenzo River, which runs through downtown Santa Cruz. Then the city of Santa Cruz might be able to provide flood warnings longer in advance, so people could sandbag their buildings or evacuate.

Statewide range

Data from the coastal network is being collected from a large enough swath of California to reveal statewide trends as well as regional details. For example, recent research has suggested that Central Coast waters are experiencing a rapid transition from being similar to colder northern California to resembling warmer southern California. Data from the network could confirm trends like these on a more granular scale.

Coastal network data could also improve our understanding of biological trends associated with coastal climate change. For example, researchers at the NRS’s Bodega Marine Reserve have documented species from southern California moving into northern California during the marine heat wave of 2014–16. Some of those new arrivals have remained even after the heat wave subsided.

Spotting trends like this can help manage fisheries wisely. If fishermen know in advance that species are on the move, they can alter their catches, plan their expeditions accordingly, or target entirely different species. This helps buffer coastal economies against the disappearance of certain harvested species.

Tracking how species shift with environmental conditions can also help scientists understand how climate change is reorganizing ecological communities.

“When those changes stick, and when they drift back, are among the major questions we’re interested in,” Palkovacs said.

A California Climate Action grant

Funding for the project comes from a $1 million award to the UC Natural Reserve System to seed multiple climate-focused entrepreneurial efforts. This is part of $100 million received by the University of California Office of the President from the state of California to support climate innovation research.

The state’s Climate Action grants are intended to fund applied solutions to California’s pressing climate needs. Repurposing decades of existing coastal data proved an ideal match for the grants.

“This funding makes a reality an idea that John and I have been trying to do for a long time,” Palkovacs said.

This story was originally published by the UC Natural Reserve System.

Media Resources

- Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu

- Kathleen Wong, UC Natural Reserves, Kathleen.Wong@ucop.edu